The soul of the trucker

WORKING AMERICA REFERENCE BOOK.

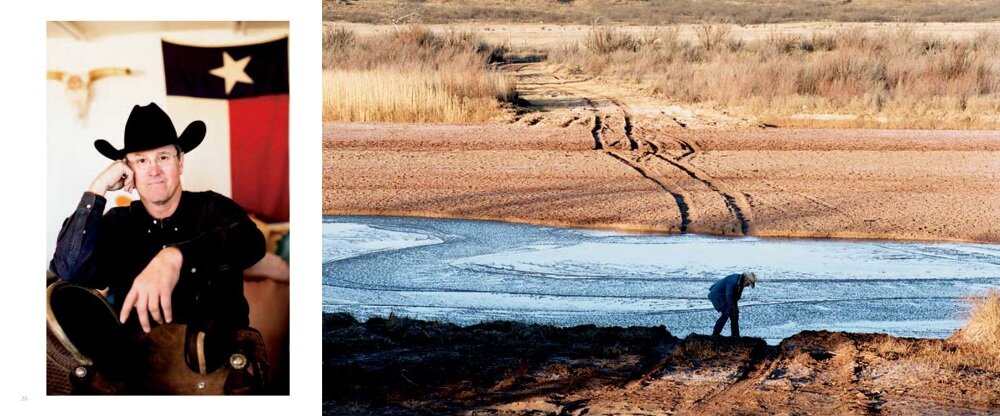

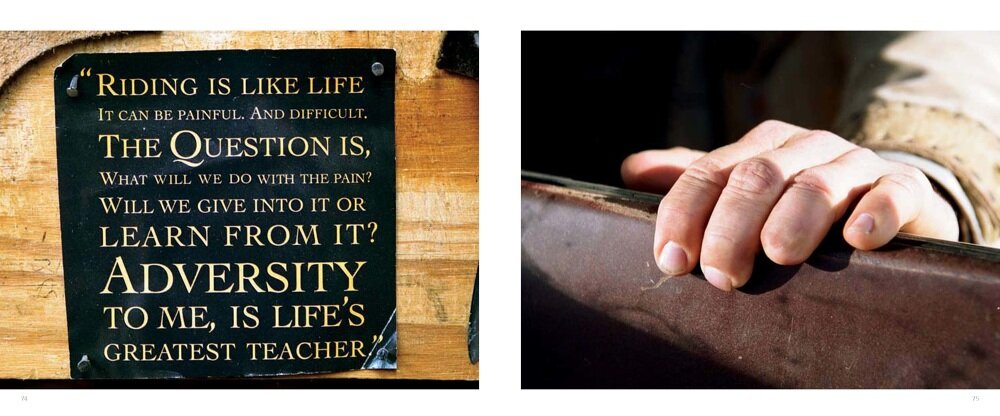

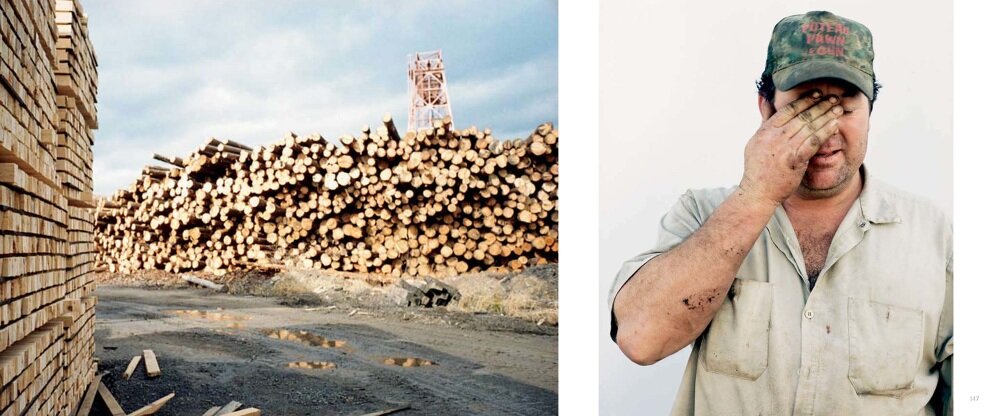

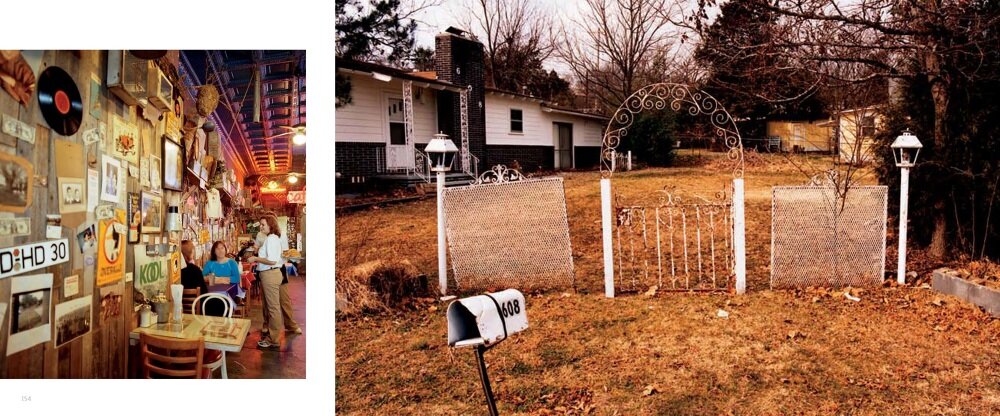

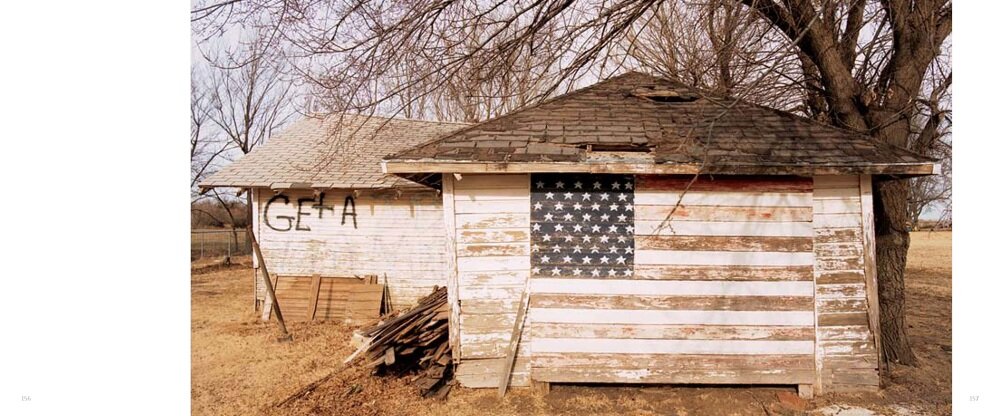

"We needed to prove we (and Toyota) had seen and understood the intimate details and textures of blue collar America, details that are beyond common knowledge - essentially the insights into their lives that we could only have learned by being there with them.

And so, the challenge with "Working America" was to do it in a way that did not seem corporate or self-serving - It had to be an authentic demonstration of respect, acknowledging the role that these honest-to-goodness workers played in the design and engineering of this truck. Being honest and authentic was absolutely key in this project". —Erich Funke

I worked on the giant project that launched Toyota's first full-size truck into the North American truck market.

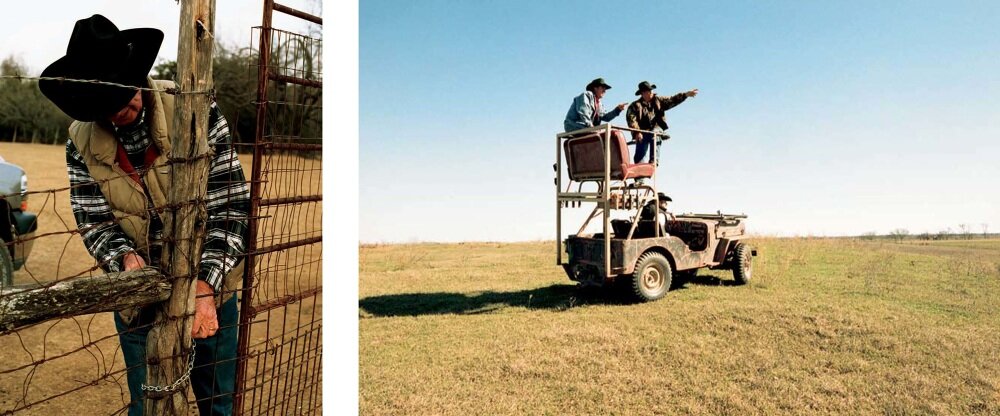

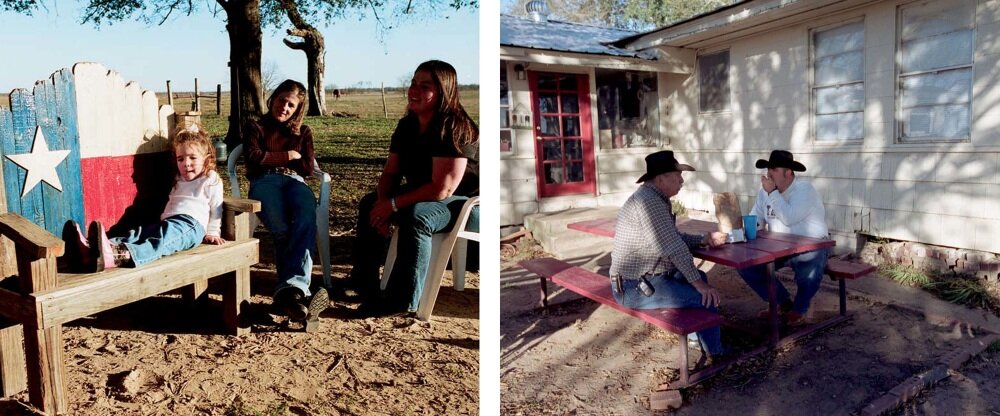

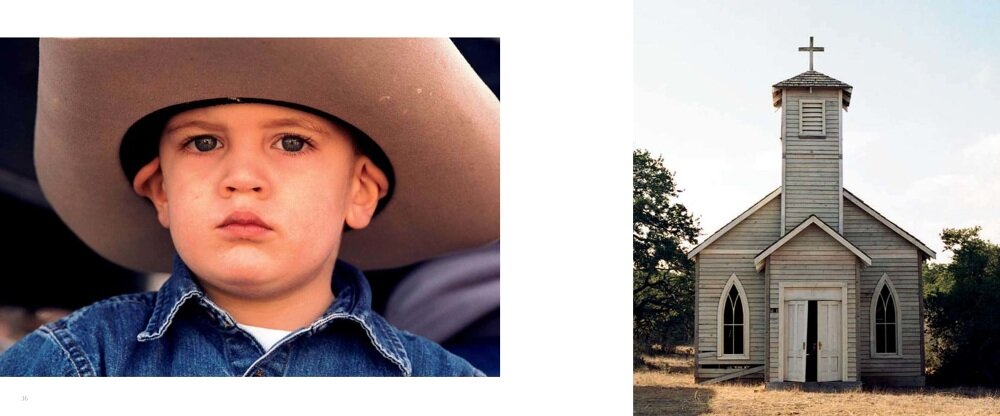

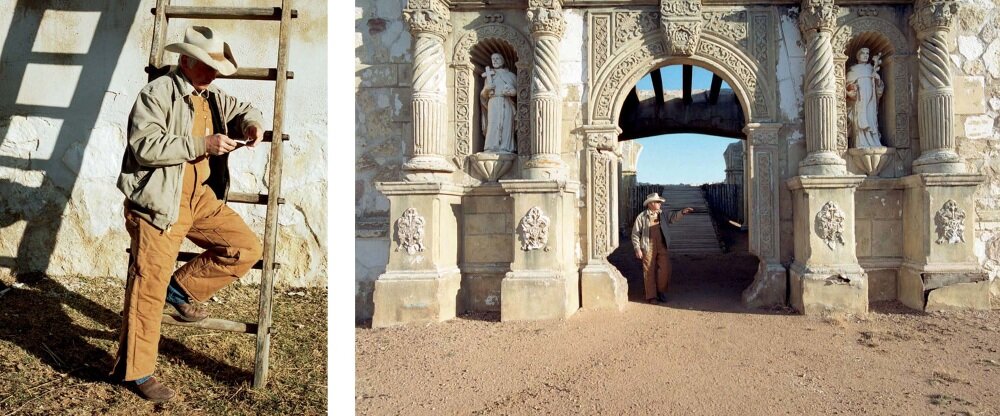

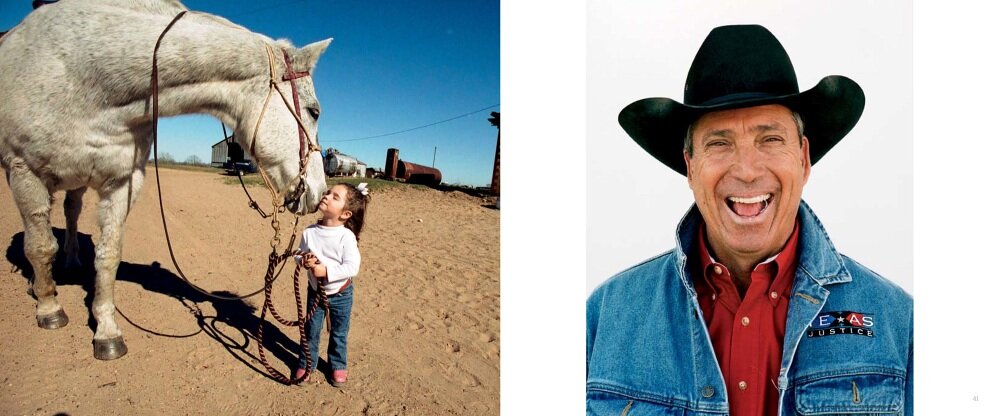

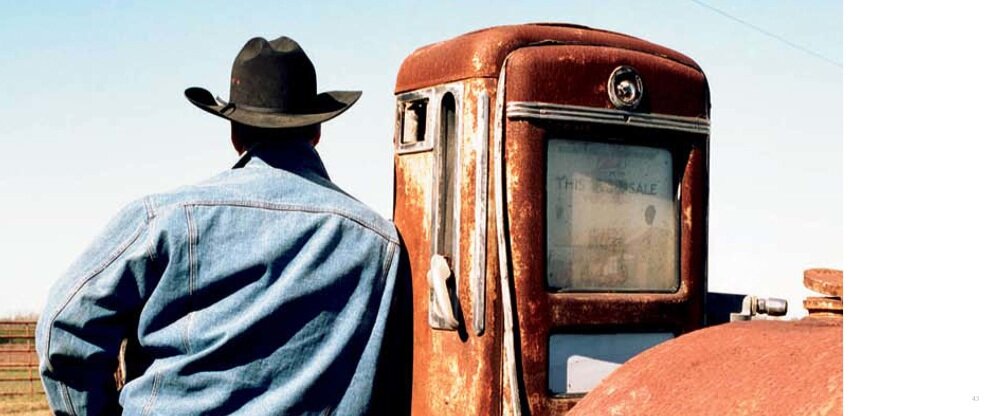

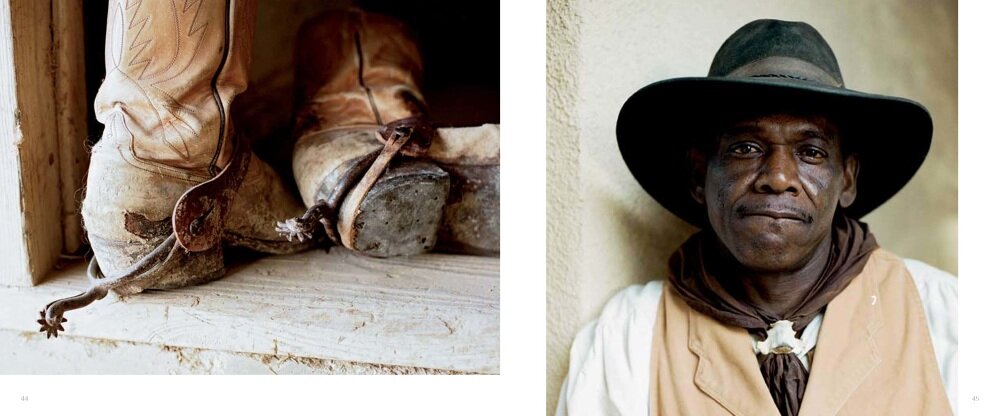

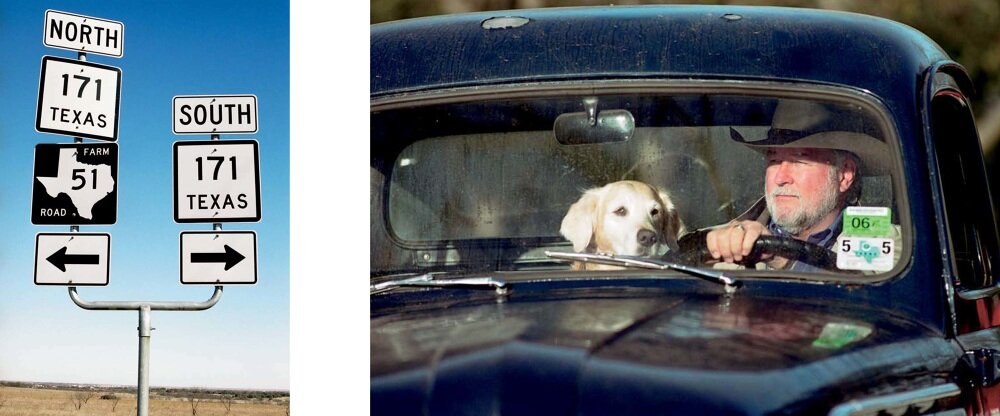

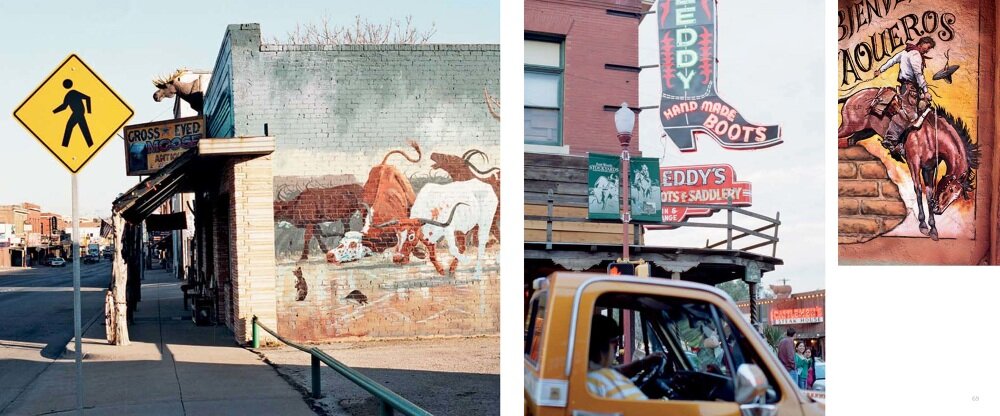

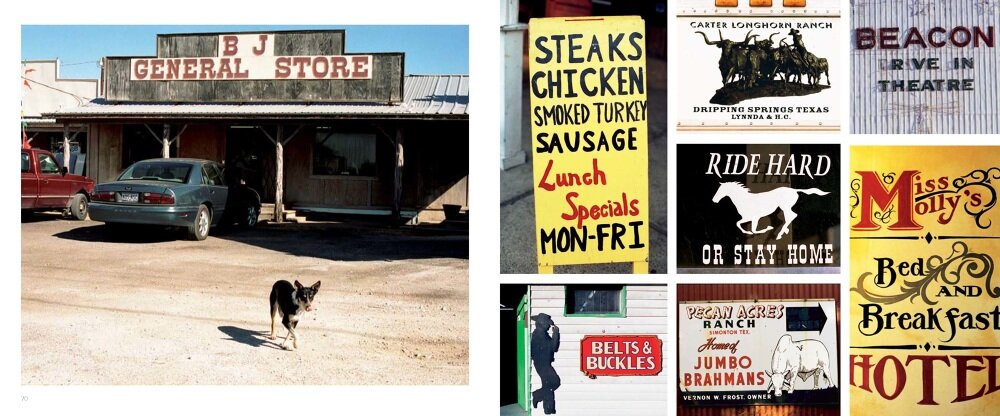

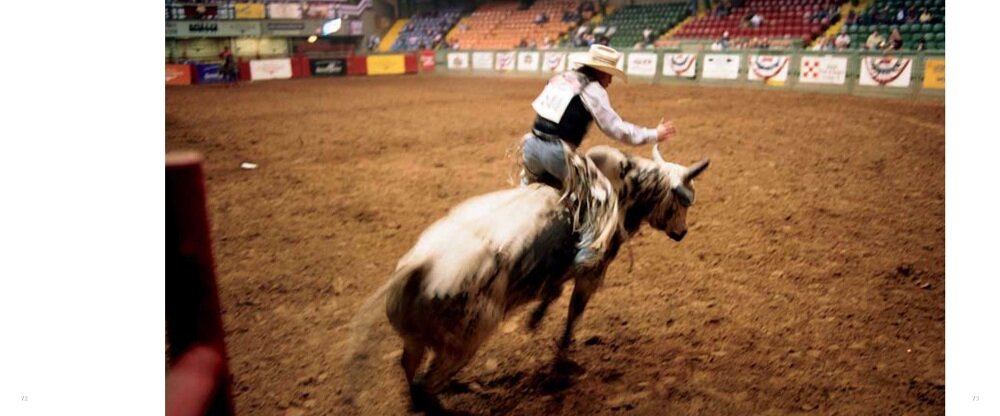

In order to learn how truck folk think, how they look and conduct themselves, I commissioned teams of photographers, writers, and videographers to visit with and interview truck folk from all walks of life.

We worked with some of the most esteemed photographers and writers in the US, and we researched and produced a 261 page coffee table book on blue collar America.

And we've used it as a reference book and trucker bible for 10 years since.

Our efforts were recognized by Fortune magazine:

“America’s Best Car Company.

Toyota has become a red-white-and-blue role model.

How? By understanding Americans better than Detroit does.”

-Fortune, March 2007.

Photographers included internationally acclaimed Jim Nachtwey, Steve McCurry, and Jeff Dunas.

Writers included Hampton Sides, Randy Wayne White, David Masiel and Bill Vaughn, with Philip Armour as editor.

I've included a selection of the essays and photography below.

Dust Jacket:

Intro:

—Hampton Sides

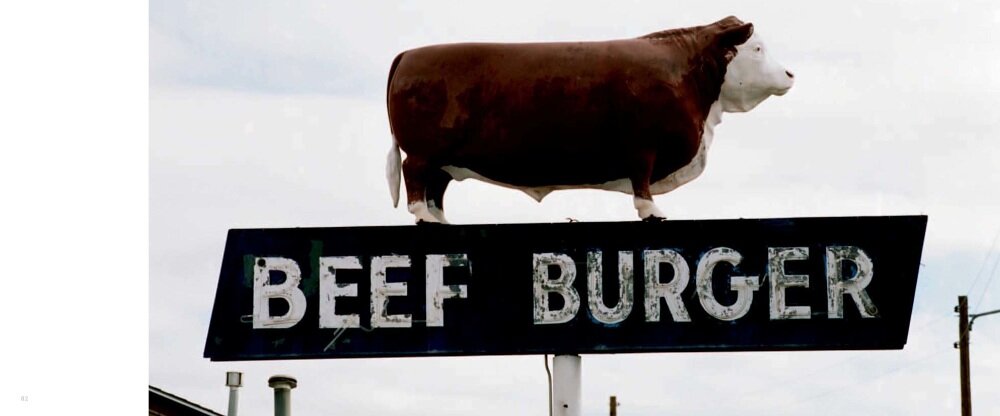

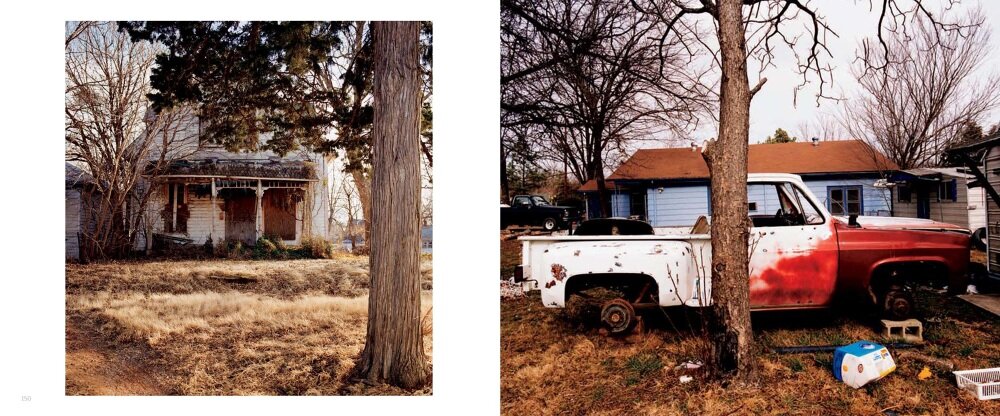

You get the idea these days that Americans don’t work anymore. That we outsource all our jobs to Calcutta or Shanghai. That we’re overrun by illegal immigrants who do tasks that produce a substance formerly known as sweat. That the phrase MADE IN AMERICA is an oxymoron.

This is nonsense, of course. Americans are logging longer hours and taking fewer vacations than ever before, and the U.S. economy seems capable of weathering anything that’s thrown at it—hurricanes, gluttonous oil barons, highjacked airliners. How is this possible? Creative accounting does not make for an economic engine this formidable. People do. And despite that we’ve entered the age of half-caf, wi-fi post-industrialism, Americans still work their asses off. It’s the shear nature of work that has changed for many of us.

One of my favorite movies is Mike Judge’s hilarious 1999 satire Office Space. It’s about how passive-aggressive and belittling office work can be, about how cubicles can crush your soul. Millions of Americans who put up with anonymity in climate-controlled jobs can relate. They too have been reduced to office drones with fax machine rage and a penchant for stealing each other’s staplers—their only respite from monotony, Hawaiian Shirt Friday. At the end of the movie, the main character finds bliss in a real job: construction. That he happily dons a hardhat, wields a shovel, packs his own brown bag lunch, says something about the need to be physically connected to work.

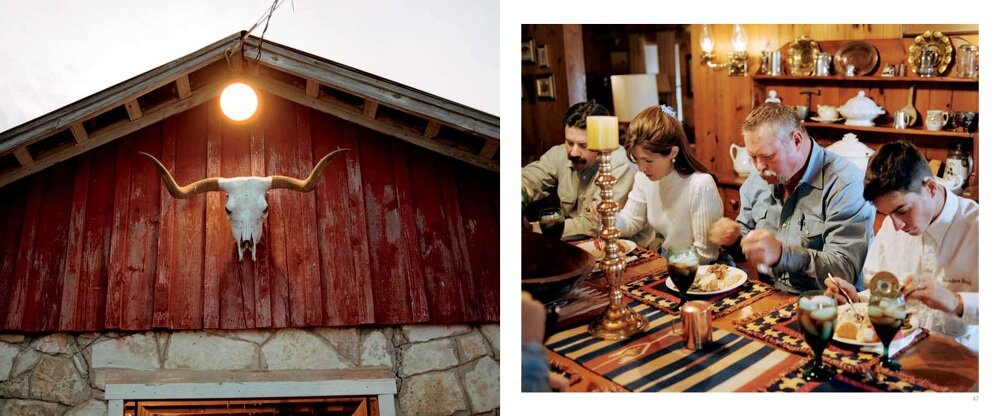

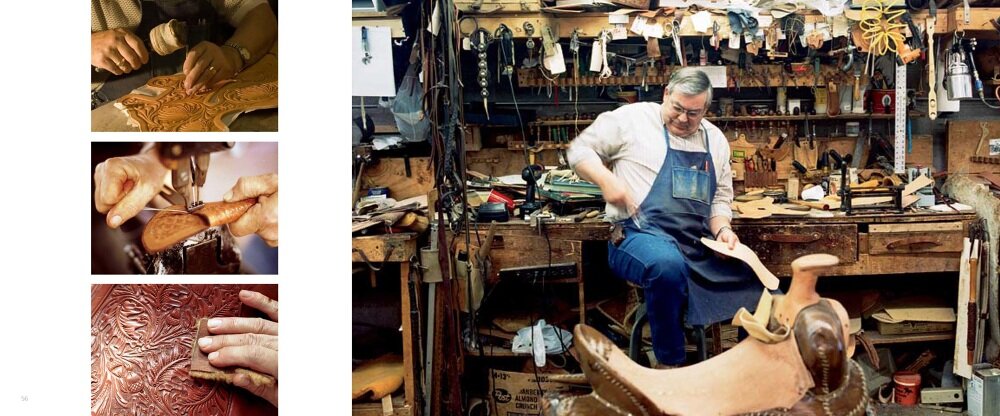

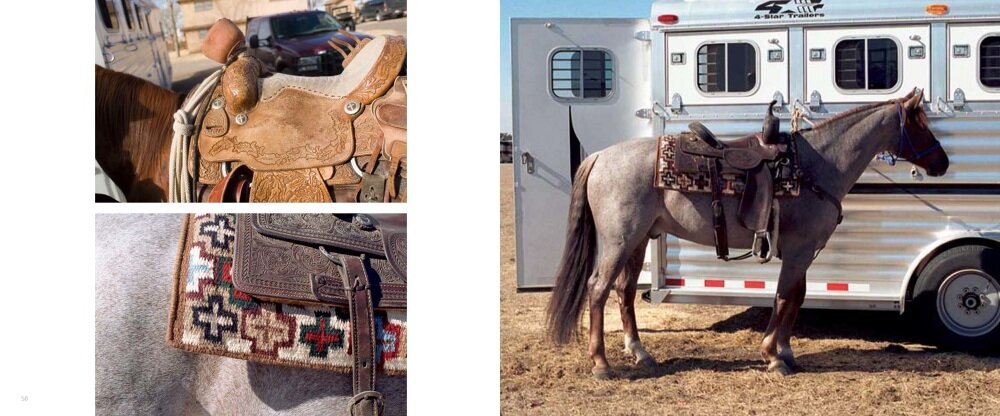

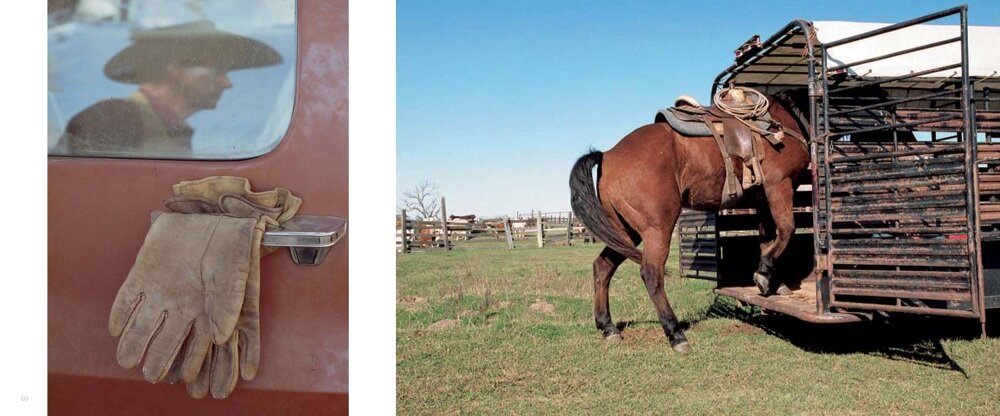

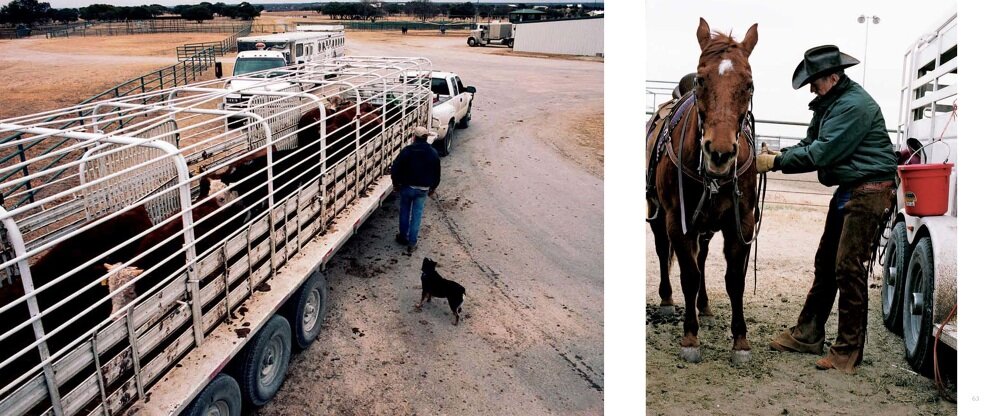

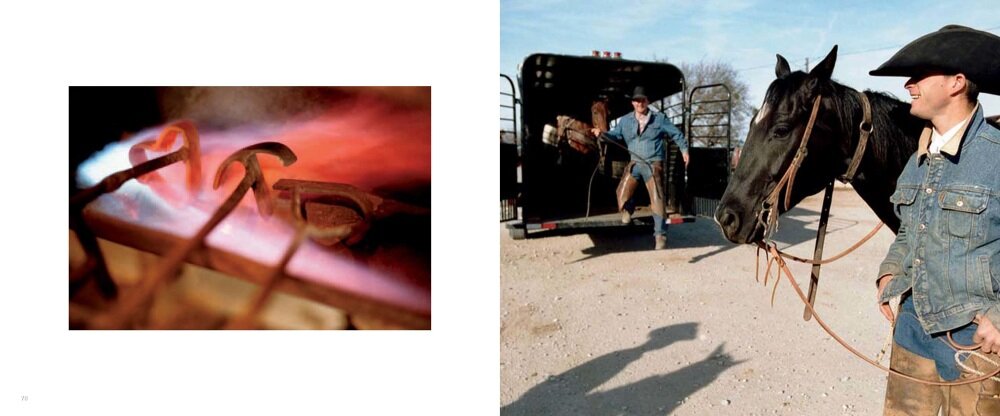

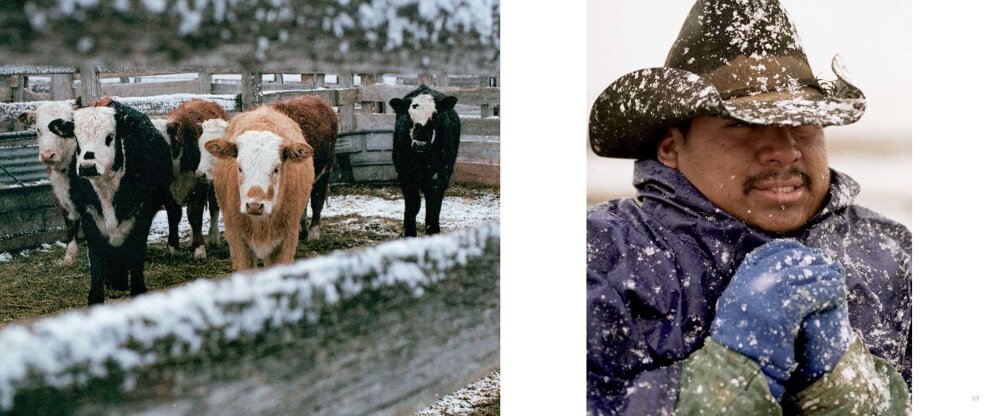

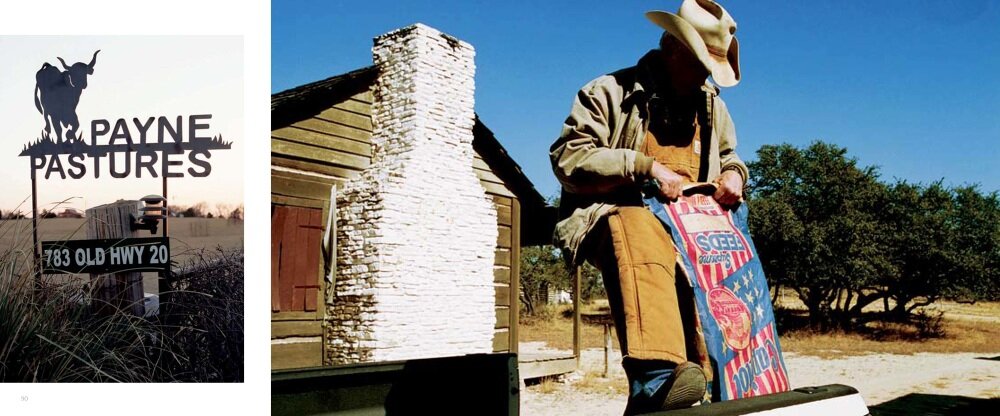

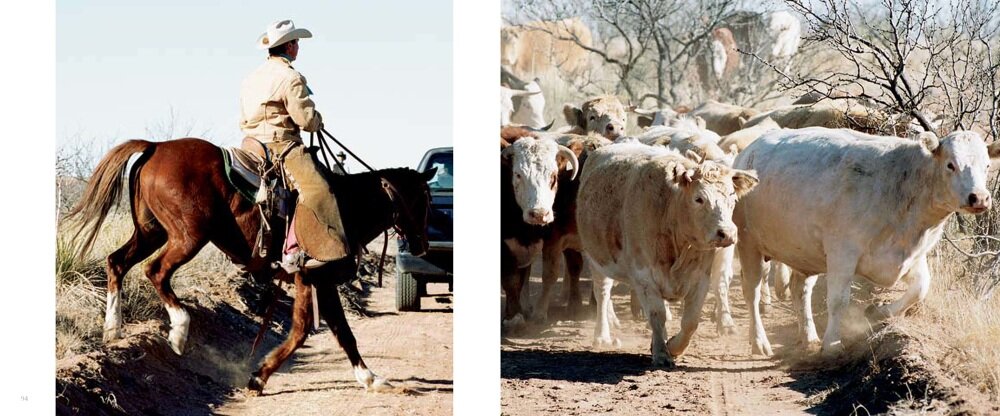

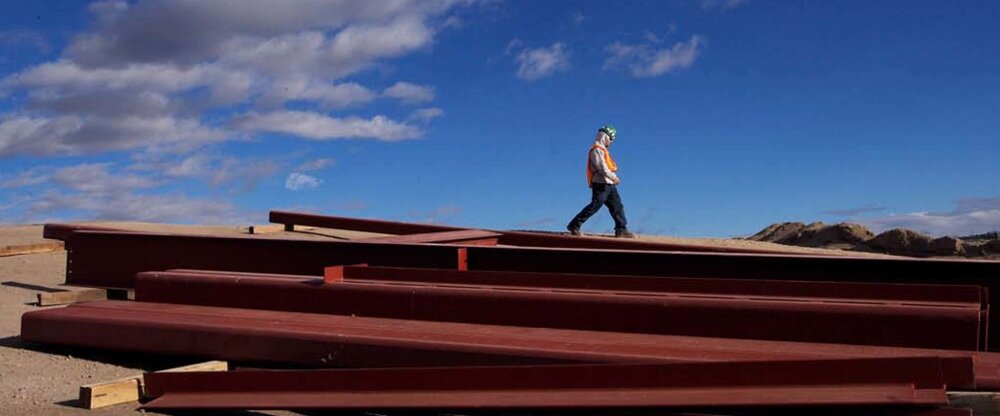

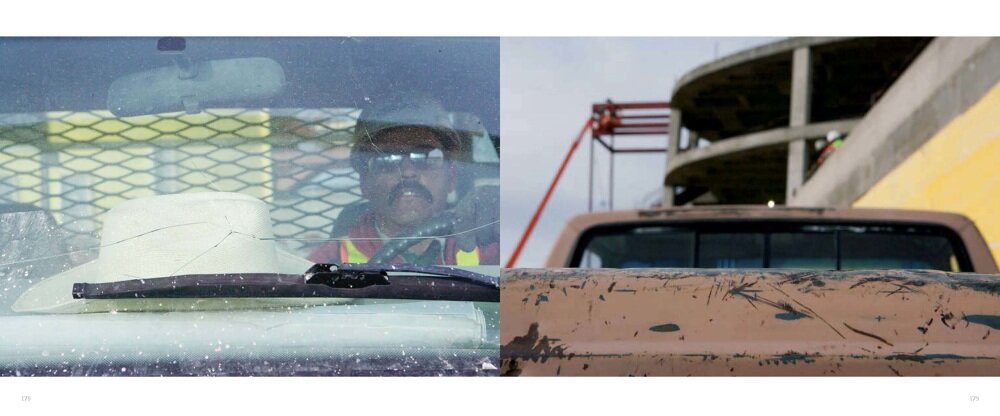

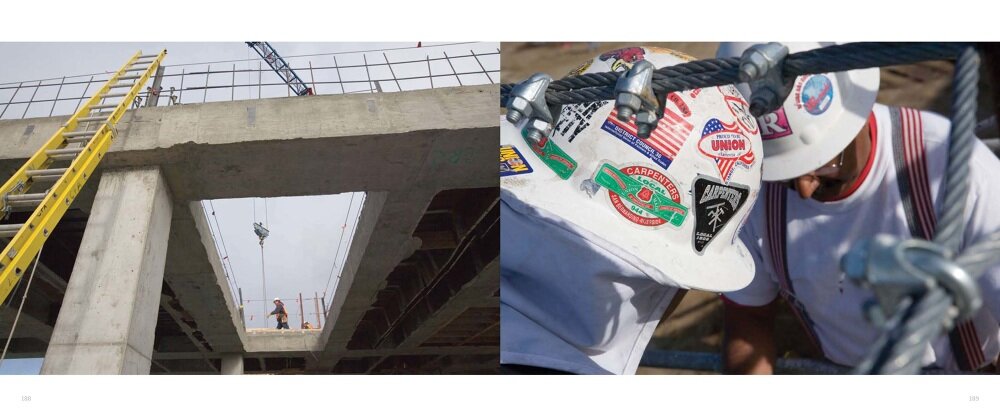

The men and women captured with such textured realism in the pages of this book work with real materials, real tools, and real muscles and represent a much larger world of physical labor that keeps this country running. The award-winning photographers whose exquisite work is presented here could have just as easily trained their lenses on stevedores, mechanics, commercial fishermen, steel workers, firemen, shipyard riveters, bush pilots, tug boat captains, or tool and die tradesmen. In that sense, our subjects are stand-ins: To look into their faces is to look into the face of all of Working America.

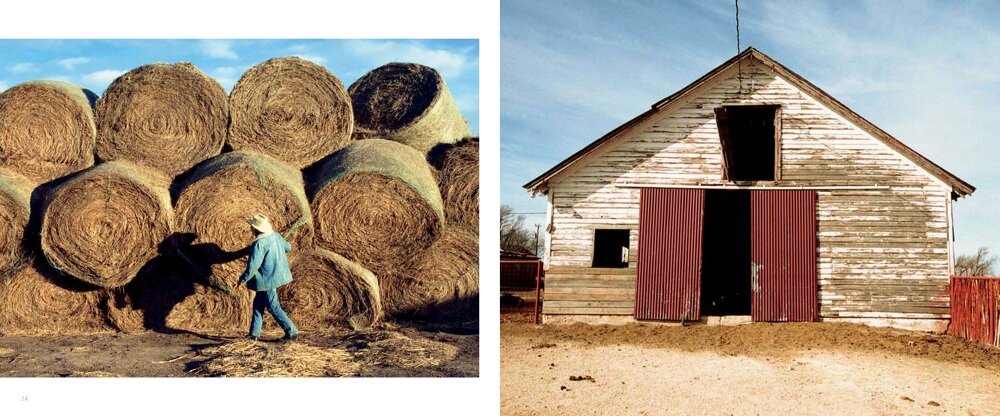

A certain concreteness—an absence of abstraction—dignifies their endeavors. There is nothing “virtual” about what these people do. The hard tangibility of their labor is matched by its conceptual simplicity. It doesn’t require much to explain what they do or why competence has value. Hay needs baling, houses need nails, and trucks need building. That’s that. If you invited a crew of miners to wear Hawaiian shirts on Friday, you might get your butt kicked.

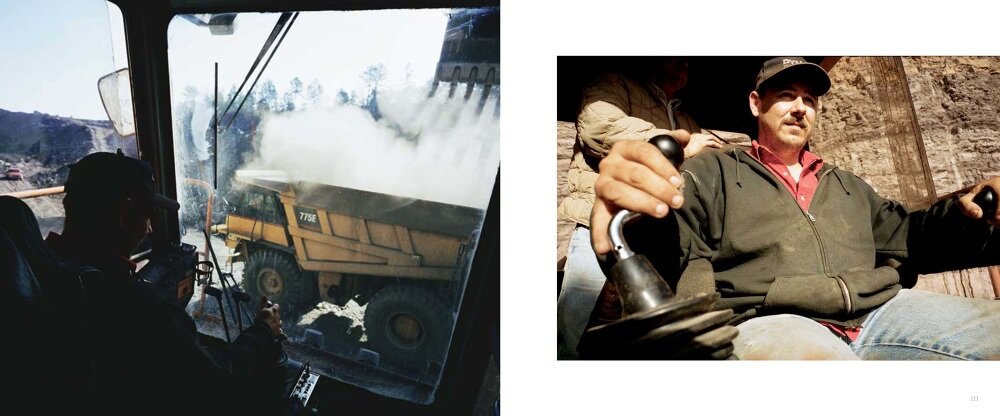

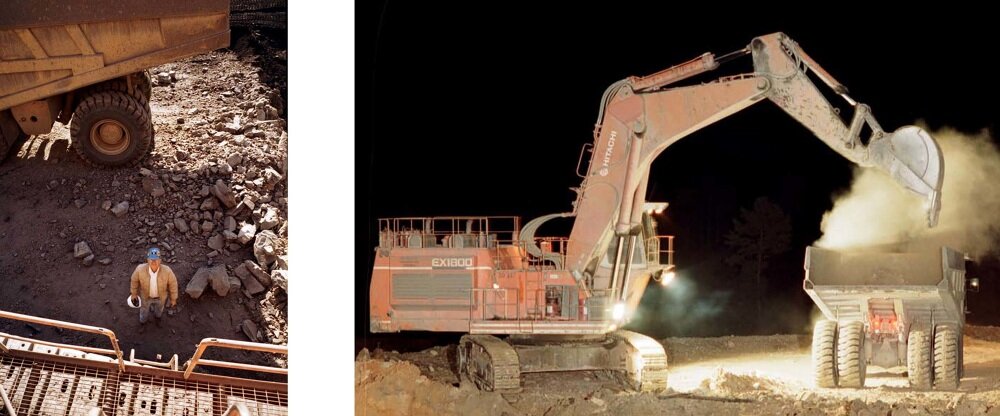

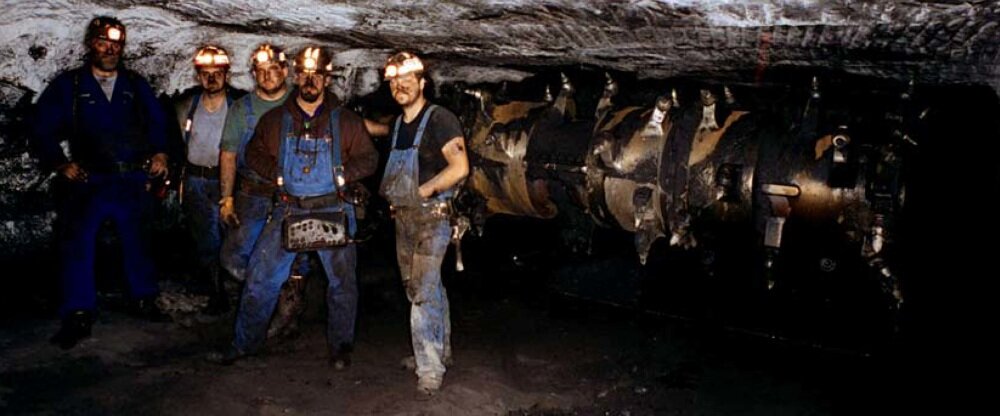

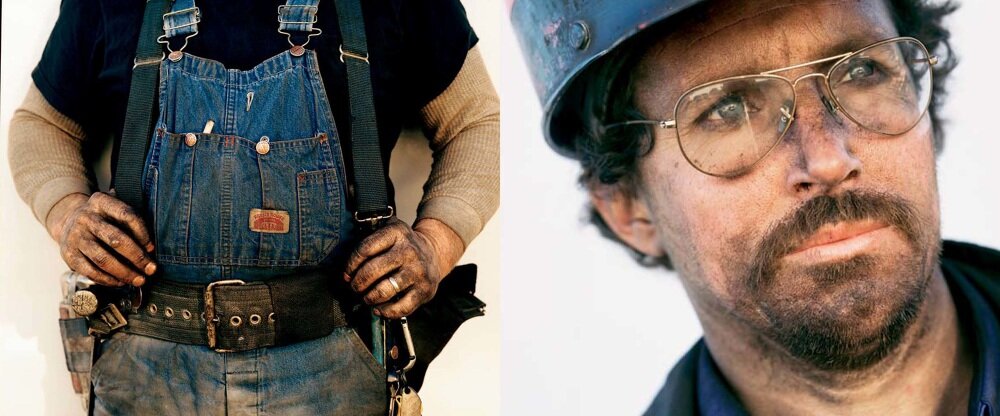

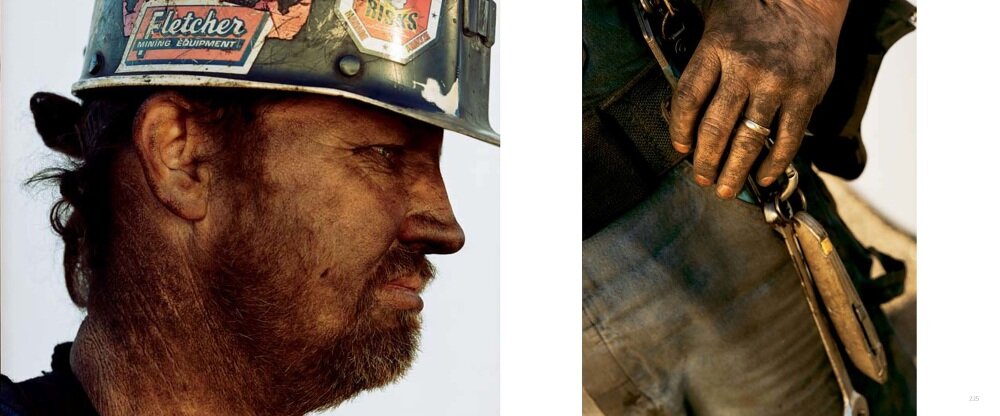

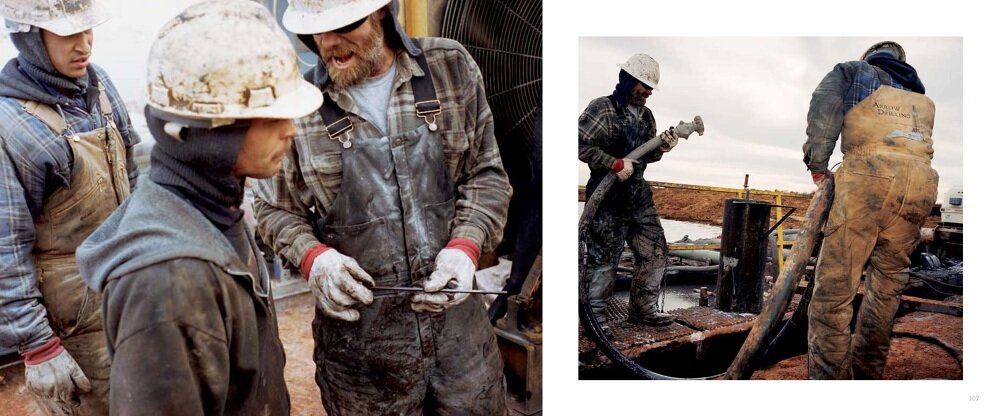

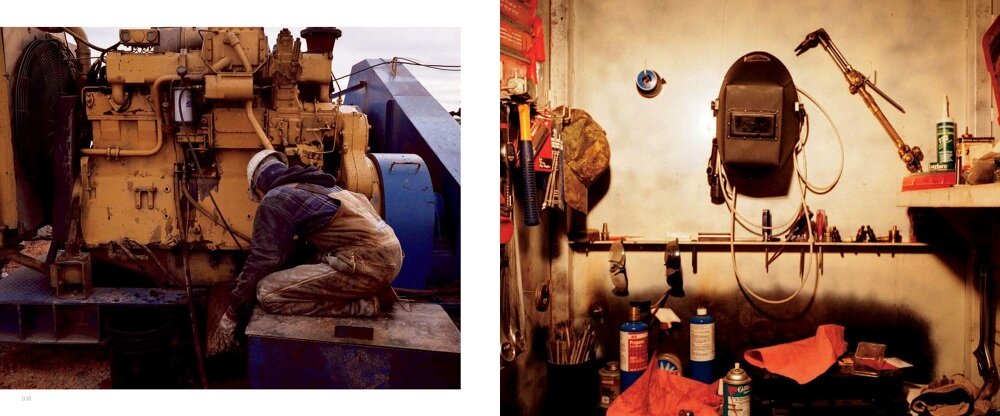

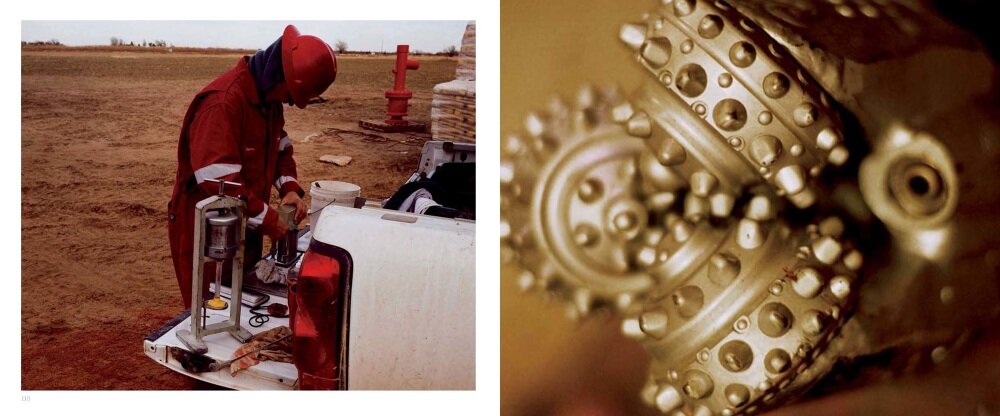

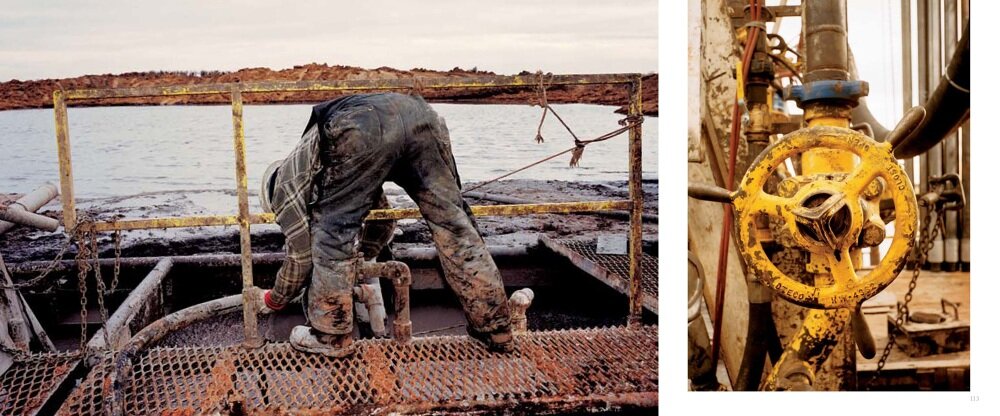

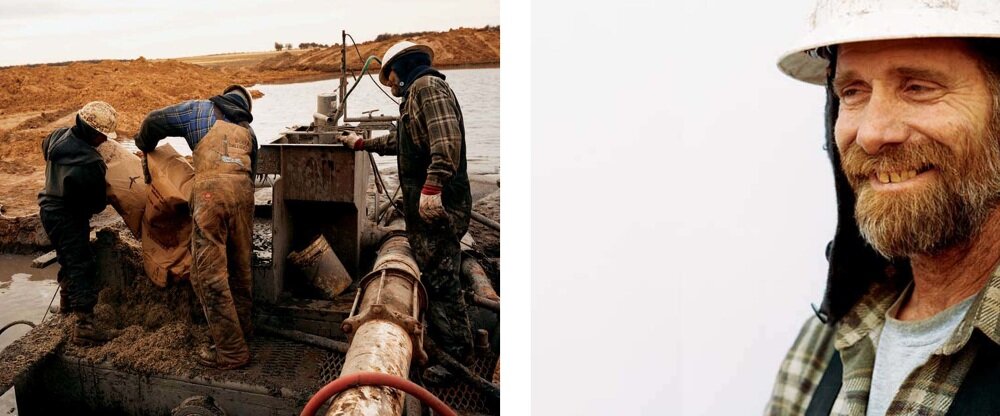

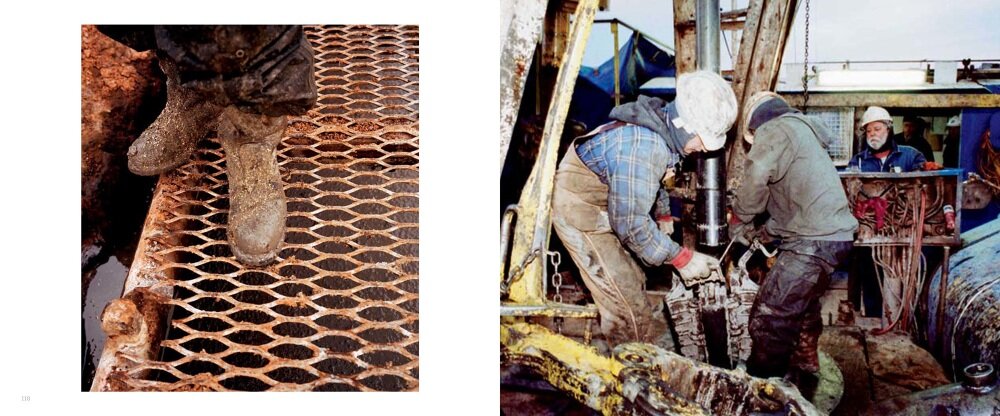

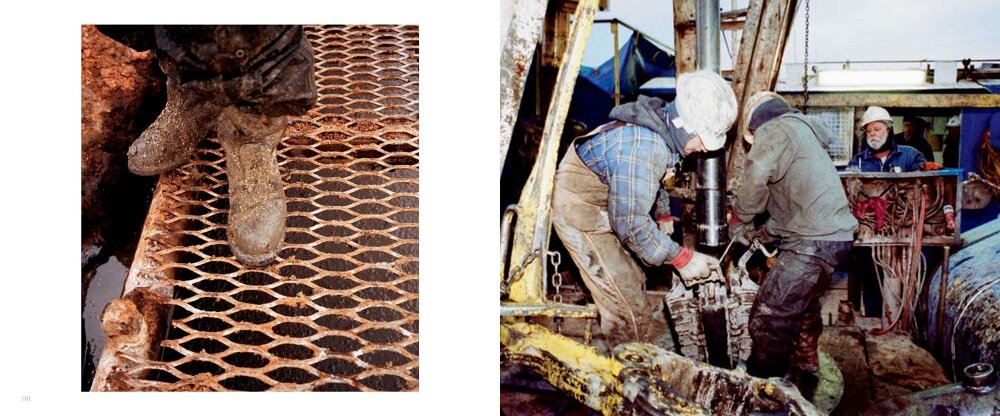

Photographers Jeff Dunas, Steve McCurry, and James Nachtwey ventured into the American heartland to document decidedly gritty lines of work. “It was a dream assignment,” says the L.A.-based Dunas about traveling through Oklahoma and Arkansas for his parts of the book. Although the equipment of coal mining and oil drilling is state-of-the-art (or “mindboggling, strange machines,” as he described it), Dunas was struck by the physical toil that remains at the heart of heavy industry. “The bottom line is that human beings are still going down into the mines every day to bring out coal,” he told me. “And oil-rigging crews are still running pipe into the ground, performing this high-risk ballet where if they’re not extremely careful and proficient, they’ll lose a hand in a second. There is a certain dignity to that kind of work. And a certain pride.”

As a journalist and historian, I can’t say that my hands are callused, or that my face is salt-etched from a hard life spent in, say, the merchant marine. I don’t wear a welder’s hooded spacesuit to go off to work. I don’t operate machinery, and I don’t risk my life when I punch in. In fact, I don’t even punch in. My seven-year-old once came to my office to watched me “work”—watched as I picked up a document, slowly l-o-o-k-e-d at it, typed a few words, consulted the same document again, or maybe looked at. . . a different document. Then, after an hour and without trying to hurt my feelings, he said, “Dad, is it always like this?”

No, it wasn’t. Every summer until I was eighteen, my brother and I lived on my MATERNAL OR PATERNAL? grandfather’s farm in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. The old man (whose hands were callused) put us to work, eight hours a day, six days a week. It was Redneck Summer Camp. We cut and baled hay, chased cattle, mended fences, built ponds, culled woods, and smoked out hornet’s nests. We bush hogged the backfields, pulled thistles, harvested the orchards and boiled apple butter by the vat. We shot groundhogs, dug ditches, put in culverts, and even planted an entire hemlock forest on the far hillside.

It is the nature of living on farms that whatever has to be done, you do it. And we did.

I remember a lot of things from those years: The sound our Case tractor made when it backfired in the morning, when the engine was cold. The afternoon storms that built on the Blue Ridge Mountains and snarled fast toward our fields. The tomato juice baths we had to give our imbecile terrier whenever she cornered a skunk by the barn. And, nearly as indelible as skunk spray, the smell of outboard gasoline on my hands, a not altogether unpleasant smell that wouldn’t come off even after the miracle of Lava soap.

Mostly I recall the tired feeling at the end of the day. Even though I might be bloody and chigger-bitten and itchy with straw, it was always a good feeling, euphoric almost. I’m not sure why, exactly. A lot of the work was mindless, and looking back on it, some of it wasn’t absolutely necessary: Shitwork, you might say. Maybe I just liked knowing exactly what I had done with myself, that absence of abstraction.

At dinner, my grandmother’s food, already delicious, tasted even better. Hunger is the best spice, after all. But in some cases, it was also because I had picked the corn or tomato or peach myself, from a garden that maybe I had also helped to plant, or mulch, or rescue from the ravages of the Japanese beetle. There’s nourishment in hard work, and even (if I may say it out loud) a certain nobility.

For the past few years, I’ve been immersed in the history of the American frontier, researching a book about the life and times of the controversial Western pioneer Kit Carson (1809-1868). Back then, everything, even the simplest daily tasks we now take for granted, required an immense amount of labor. Washing, cooking, traveling, making candles, making soap, butchering animals, tanning hides took time and effort. Physical exertion, by humans and animals alike, was the coin of the realm.

This sort of life made men and women tougher and more self-reliant, but it also took a toll. It plain wore people out, broke them, and hunched their backs. If you didn’t keep your mind on your business, you starved. The ache of effort was a constant companion, and one inescapable truth runs through the old daguerreotypes: To be alive was to work.

I can see some of the same qualities in the portraits found in these pages—a leathery toughness, a stoic gleam in the eye, a satisfaction with the world cut with a receptivity to pain. While the nature of the physical labor has changed greatly since the 1860s, for those who do it day in and day out, the faces look much the same. What has changed is the blind rush for natural resources and unbridled industry. Our 21st-century sensibilities have somewhat tempered our 19th-century passions. The raw materials, we now realize, are finite, but our ingenuity is not.

The pages to your hands, the paper, the ink, and the glue came from the earth and from people using their hands. Savor these photographs. It is a treat to have such fine photographers turned loose on such vital subjects. As the images emphatically attest, rumors of American labor’s demise are much exaggerated.

—Hampton Sides, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2006

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~••••ooooooo||||[O]||||ooooooo••••~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

INTO THE DARKNESS

— Randy Wayne White

America's history is forever linked to the extraction of wealth from mine shafts and strip canyons, which illustrate, strata by strata, the slow geological cataclysms that formed this planet—as well as the scarring our species has inflicted on it to establish dominion. Paleolithic man first coaxed a spark from earthen tools and created fire 800,000 years ago, and generation after human generation has developed tools of increasing complexity ever since, including today’s dinosaur-sized machinery (an unfortunate analogy if theories about global warming turn out to be accurate).

For two centuries, coal was king. As a cheap, abundant fuel source, it powered the engines, forges, and furnaces of the Industrial Revolution. Coal was so profitable it catalyzed technological advances and increased 19th-century industrial production, amplifying its demand in proportion. This pitted mine owners against coal miners, who responded by forming trade unions and lobbying for humane hours, a living wage, and safer working conditions—requirements companies refused to meet… at first.

America was so dependent on coal that a strike by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), the country’s most powerful union, could effectively shut down the nation. Newspapers across the country feverishly reported details of these conflicts, articles read by the light of coal-gas lamps, in the warmth of coal-fueled furnaces, in homes stocked with appliances and food delivered by coal-fired steam locomotives. Industrialists and politicians had no choice but to negotiate. In this way, mining not only fueled the Industrial Revolution, it helped pioneer the social revolutions of the 20th century.

John L. Lewis, the legendary president of the UMWA, used to live on an island off the southwestern coast of Florida and, as it turns out, owned the old house next to mine. Florida's warmth and light attracted this lifelong miner for a reason. Descend into the black and claustrophobic conduit of a coal shaft and the expression “colder than a well-digger’s ass” immediately strikes home.

According to locals, Lewis loved the island so much, and his power was so great, that he imported a whole town of coal miners to blast a channel through the shallow bay that fronted his property—a channel my boat and I use often. Lewis also strong-armed President Franklin D. Roosevelt into building a post office in this isolated place just for him. FDR was nobody's fool and ordered it done, perhaps to keep his strike-loving nemesis on vacation and away from labor union rallies.

My colorful neighbor, and the fact that I get my mail each and every working day from that little one-room, board-and-batten post office, inspired me to learn more about the history of mining. Stepping through that door is like stepping back in time. The creak of wooden floors and the sheen of brass and gilded lettering evoke the burble of Model A’s, FDR's radio speeches, and the ubiquitous clank of a coal-fired stove. Though coal-powered power plants still provide much of the nation's electricity, some say the future of mining is bleak. Something that will never waver, however, is the granite-tough spirit of mineworkers like John L. Lewis and the inexorable mettle of their collective family.

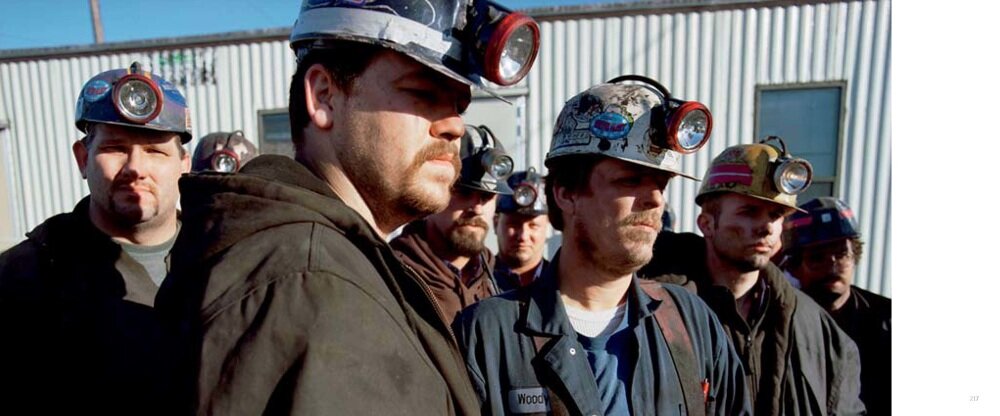

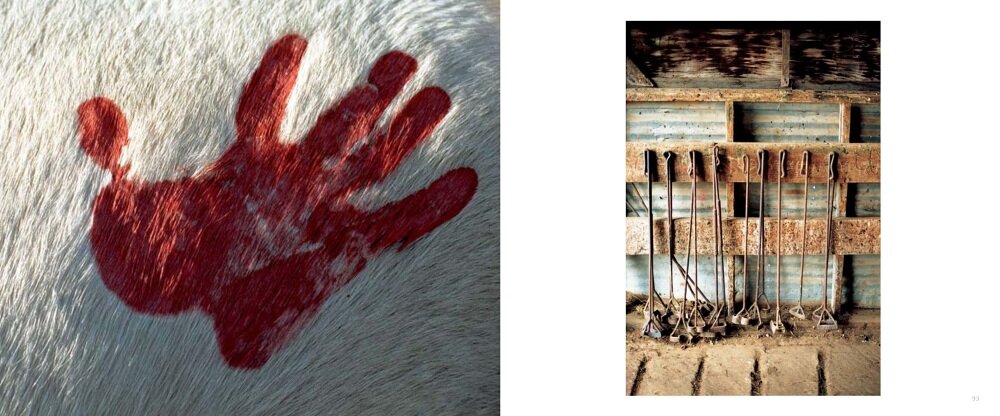

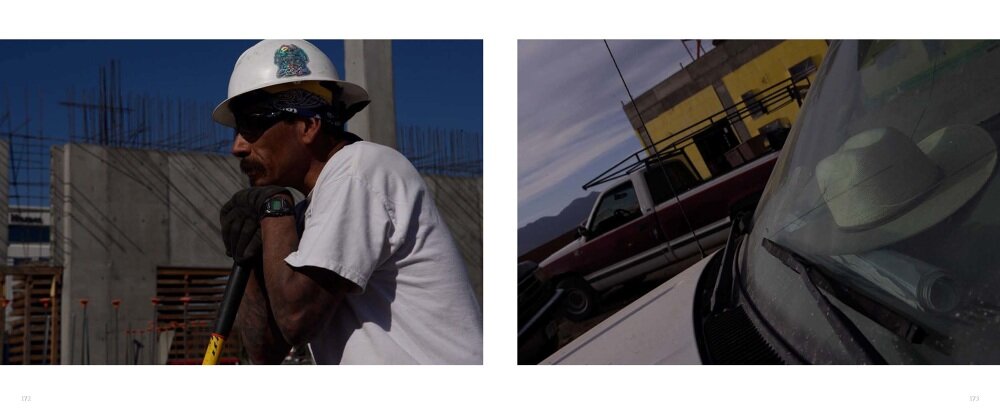

Mine workers tend to be a fun-loving, hard-working, hard-living brotherhood. The uniform of choice—hard hats, tool belts, and denim coveralls—is rugged as the faces of men who wear them. Miners are bonded to one another occupationally and socially, and by an awareness that deep earth gives, but it also takes. Mining takes sweat and strong hands. It takes blood. Mining takes men's lives.

Since the earliest days of hard-rock mining (the removal of ore directly from its host rock) and quarrying coal, underground work has been one of the world's most dangerous occupations. From 1880 to 1910, mine explosions and other related accidents killed thousands. 1907 was the deadliest year in U.S. coal mining history, when 3,242 men died in the darkness. According to US Bureau of Labor statistics, the coal industry averaged more than 1,500 deaths annually in the early 1900s. Union demands and legislation caused the figures to gradually decrease, with fewer than 500 deaths annually in the 1950s, 200 in the 1970s, and fewer than 50 deaths a year in the 1990s, although there were 87 fatalities in 1999.

But the mining tragedies of 2006 remind us that the profession is still dangerous. Deep earth is forever unforgiving. Miners know. So do their families. Poet Carl Sandburg wrote of the "white-cauliflower faces of miners’ wives waiting for the men to come home from the day's work."

Today, about 71,000 people are employed nationwide in the hard-rock mining industry and 112,500 in coal mining, numbers that include executives, geologists, salespeople, and office support. Fewer than 100,000 men do the actual physical labor of splitting rock and extracting the raw elements that collectively provide us with insecticides, disinfectant, fungicides, gas, billiard balls, mothballs, fireproofing, food preservatives, paint thinner, soda water, prescription medicines, synthetic rubber, wood preservatives, varnish, glue, baking powder, perfumes, linoleum, artificial silk, sugar substitutes, explosives, and fossil fuels.

Over a space of 300 years, “Miners Trapped!” has become an unwelcome but familiar American headline. The faces of miners’ wives still fade cauliflower-white at the news, yet their resolute men continue to venture into darkness and bring this nation light.

— Randy Wayne White

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~••••ooooooo||||[O]||||ooooooo••••~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

MONTANA FALL

— Bill Vaughn

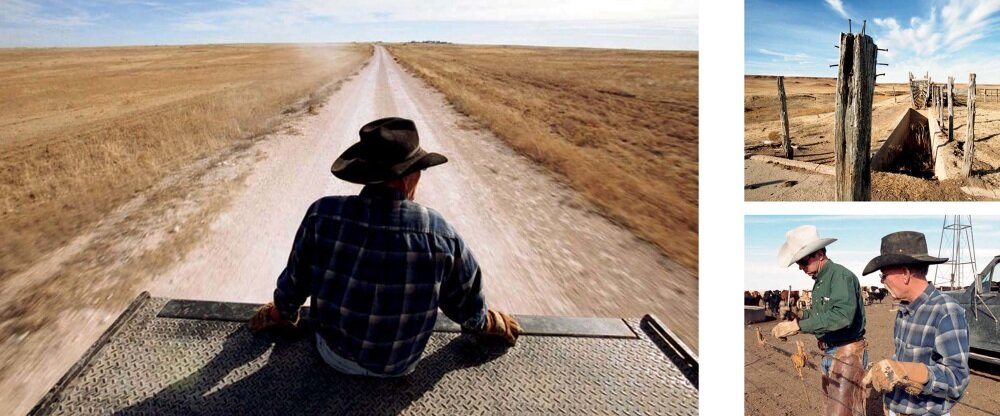

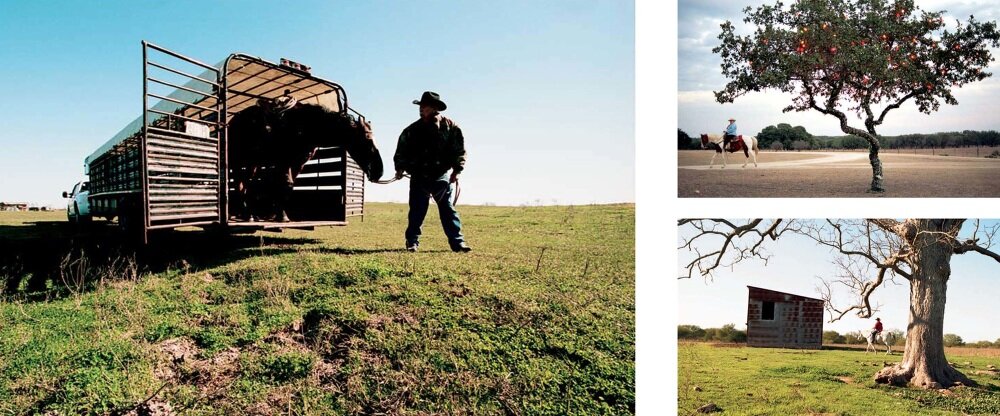

It must have been a cow, that stubborn thing hiding in a tangle of scrub. At least that’s what I figured was causing my mare’s wild eyes and racing pulse as we walked our horses down to surround all but the thicket’s lowest side. Kitty, my wife, took the left flank, and Jerry Hamel, owner of the ranch, the right.

You’d think three mounted people would be force enough to convince an ordinary heifer to flee. Especially because she would have seen that the other strays we’d extracted along this ridge were leaving her behind, plodding toward a holding pen at the intersection of two fence lines below us in a meadow. But after we hollered and whistled and flapped our coils of rope nothing happened. A magpie yelled back, then flew away in a huff.

With a click I urged Timer forward, expecting the same enthusiasm for the work she’d shown all day. Instead, she scotched. Then scotched again. After another of these lateral moves at the line of scrimmage I stopped pushing. Whatever was lurking inside those junipers and chokecherries, it wasn’t a cow.

Until someone clones a bovine that’s immune to disease, born with a brand and an ear tag, and knows when it’s time to move herself from summer to winter pasture, the daily labor of beef growers will remain essentially the same as it was when the founders of my family, and those of Kitty’s, began ranching not far from here in the 1870s. My great-grandfather, Thomas Moran—landless, illiterate, and persecuted for being a Catholic—escaped County Waterford, Ireland, when he was 19 and fled to the U.S., where he found work as a farmhand near Boston. After he was rejected for service in the Civil War by a recruiter who claimed the Irish weren’t even good enough for cannon fodder, he sailed off, furious, to San Francisco. He ended up milking 50 cows twice a day, falling asleep with his swollen hands soaking in pails of water. After hearing about a big gold strike in the Montana Territory he headed north with another man, taking turns riding one horse.

In what would become the Treasure State, he prospected in the Highwood Mountains and all along Last Chance Gulch. In January of 1866, he joined 1,500 gold-crazed fools chasing a rumor of another mother lode, a rush across the territory that was cut short by a horrific blizzard. Temperatures plunged to 40 below and froze some prospectors solid. Moran’s hide was saved by Italian Jesuits at St. Peter’s Mission, a squalid collection of cottonwood shacks on the Missouri River.

That spring, after the Blackfeet began killing settlers and shooting their cattle, Moran helped the fathers move St. Peter’s to a boxed valley ringed by massive stone buttes carved by the elements into antic shapes. Haystack, Birdtail, Lionhead, Fishback and others still dominate the skyline. But the day after the new Mission was dedicated, the “Black Robes” ran away again, still fearing for their scalps. They left Moran behind as caretaker. He kept his hair because a friend, who also elected to settle at the Mission, had married the daughter of Heavy Shield, a Blackfeet chief.

When the Jesuits returned eight years later, Moran poured his relentless energies into acquiring the three things he’d been denied by the tyrannies of the English Crown. First, he built a small church from roughhewn timbers. Then he convinced the fathers to teach him how to read. Finally, he began buying land with a joyful vengeance, leading some to wonder if he’d struck gold after all, or maybe discovered loot hidden by stagecoach robbers working the nearby Mullan Road.

His 1,700-acre spread was tiny by Montana standards, but more productive than places ten times its size, because the pastures were cobwebbed with finger creeks and steeped in thousands of years of bison manure. He married and did a sweet business selling grain, hay, and beef to the stage stations and to the U.S. Army garrisoned at Fort Shaw. He was the first farmer in the area to buy a Wood’s binder, a house-sized implement pulled by horses that threshed grain and bound it into sheaves. In an era when few frontier people had any schooling, he sent his three daughters and my mother’s father to Gonzaga University.

Kitty’s great-great-grandfather founded his fiefdom on cattle his clan stole from the ranch they were managing for a corporation back east. When the old man decided they ought to branch out, he divided this pilfered largesse equally between himself and his two sons. The younger, Holly Herrin, took 320 acres, 53 cows and 12 horses and set forth to make some real dough. He expanded into the butcher business and ran meat wagons to the mining camps. He bought and sold progressively larger places until he’d patched together one of the biggest spreads in Montana, the Oxbow Ranch. You could walk all day through those terraces along the Missouri, and when it was time to curl up by the campfire you’d still be on Herrin land. Instead of fighting the sheep men moving into the territory in the 1880s, Herrin joined them and built his flock to more than 13,000 woolies. He was equally famous in the area for being the only man to lift a 500-pound keg of nails at Fourth of July festivities in the village of Wolf Creek.

Alas, all empires fall, either with a crash or, in the case of our great-grandfathers, with a sigh. Moran’s descendants had no taste for country life and moved to Great Falls when the ranch began to fail. There are now scores of us, more people than any single cattle operation could support. All that remains of St. Peter’s is the church, standing forlorn in an Angus pasture; the shell of an opera house built for the music-loving friars (now used by cows as a windbreak); and the charred ruins of the great stone boarding schools operated by the Jesuits and the Ursuline nuns to “civilize” the Blackfeet and Métis. Old Tom Moran’s headstone leans in the cemetery on a hill above the church.

Holly Herrin’s second wife cheated on him with the man who would later mastermind a bank seizure of the Oxbow Ranch. Only 1,000 acres in the Helena Valley survived, the Herrin Hereford Ranch, where Kitty grew up riding horses and bossing around cows. But that property was doomed as well. Kitty’s father had an affair, a fact Kitty learned about when her mother drove down a country road and stopped by an unfamiliar mailbox to shove in a pair of the other woman’s high heels. Her parents divorced, and the ranch fell into financial ruin, and finally the courts. Kitty, her mother, and her four sisters were evicted.

Only two things were passed down to us from our great-grandfathers: a photograph of Thomas Moran in overalls—intense, bearded and haunted-looking in the manner of homeless men who live in shipping crates—and a windup Ingraham clock from Holly Herrin, which stopped at midnight a few years back.

While the ten acres Kitty and I scraped to buy sometimes make us wistful for all that land other families still own, at least we have a home for our quarter horses, that genius invention of ranchers. And there’s a certain justice in the reversal of fortune our families endured. After all, the ground that gave them their wealth had been stolen from the Indians, a larceny Moran was reminded of while out riding one day. He came across the scene of an old battle between the Blackfeet and their rivals from across the Continental Divide, the Flatheads. Outnumbered, the Blackfeet had retreated behind a crude palisade of timbers and rocks they’d thrown up. But their defense failed and they were slaughtered to a man. Moran took home a macabre souvenir, an act of grave robbery that gave Skull Butte its name. I wonder what he felt when he held up that skull to the light.

Of course, the settlers didn’t take all the land. Jerry Hamel, the rancher whose strays we were rounding up above the Jocko River, is a descendant of the men in that ferocious Flathead hunting party. Maybe because his big chestnut gelding felt more comfortable on his home turf than our horses did, Hamel was finally able to convince him to step into the thicket. Kitty and I guarded the flanks and waited, our minds wandering.

An autumn breeze hissed through the crowns of the ponderosas. North across the National Bison Range and the Flathead Indian Reservation, a higher wind shredded a few bright clouds against the rocky tops of the Mission Mountains, a row of dinosaur teeth already gleaming with early snow.

The mountain lion that bolted from the thicket was gone so fast its huge yellow eyes and flickering tail seemed like a mirage. We looked at one another, dumbstruck.

We would talk about this later. But right now, there was still work to do.

— Bill Vaughn

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~••••ooooooo||||[O]||||ooooooo••••~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

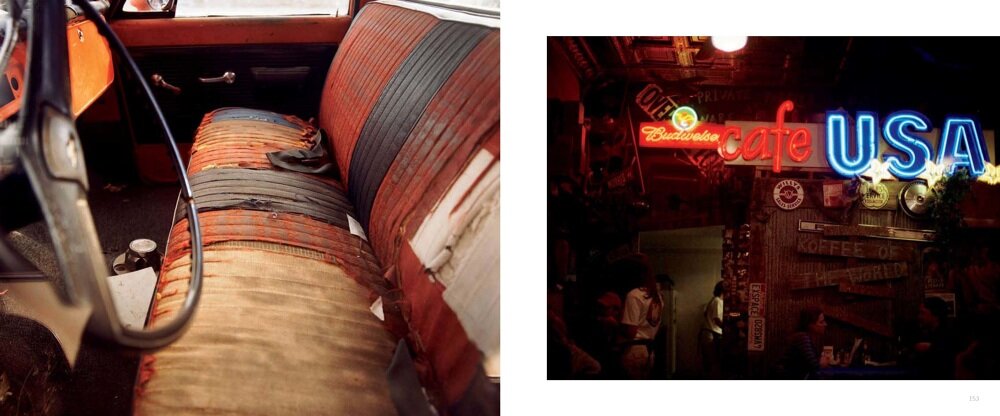

OF ROUGHNECKS AND ROUSTABOUTS

— David Masiel

Northeast of Prudhoe Bay, on Alaska's arctic coast, lies a pancake-flat gravel island called Cross Island, so-named for a tall wooden cross put up by 19th-century whalers. Over the years, people have carved initials and dates into its weathered base, a record to outlast their experience in the far north. My first visit to Cross Island came when I worked on a tug-and-barge crew that moved a drill rig onto the island’s southwestern side. We had pushed a barge into the beach and set a ramp down for offloading. I ran a front-end loader, carrying drill pipe to a staging area alongside rows of living units, light stands, and diesel generators.

This is where I met my first driller. A scruffy-faced, thin-as-wire man of indeterminate age, he wore oil-stained coveralls and a hardhat bearing the stickered logos of oil-field service companies and drilling outfits. I don’t remember his name, but he chewed tobacco, hailed from Oklahoma, and wondered out loud if I couldn't run that damned loader any faster.

"What kina longshoreman are ya anyhow?" he wanted to know, spitting tobacco juice on one of my big balloon tires.

"I'm not. I'm a towboater. What are you?"

"I'm a driller.”

"Yeah?" I teased. "Whatcha drilling for?"

"Drillin' for a new longshore crew!" he boomed and shot me a tobacco-stained grin.

On my next break, I found him on the tugboat getting a cup of coffee. He told stories in his panhandle drawl about working as a roustabout for wildcatters back home, the lowest grunt labor on the rig. For five years he’d worked on offshore production rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, doing the dirty, greasy work of a roughneck, throwing chain to make up the lengths of drill pipe, getting his hands right in there.

"Wasn't like now," he said, showing me a stump where his left index finger used to be. "They got mechanical roughnecks now. Guys these days wouldn't last throwing chain."

Already an old hand at 28, he’d worked his way up to the only job he'd ever really wanted: driller. From behind the drilling console, via a dizzying array of switches, dials, and pneumatic and hydraulic gauges, he monitored the well bore. He ran the operation. It didn't matter that he reported to the tool pusher (the rig foreman), who in turn reported to the company man. There was nothing more central than the drilling station.

His excitement was palpable as we watched construction crews erect the derrick, rising up over the flatness of Cross Island like an industrial counterpoint to the whaler's cross.

"I reckon there's nothing to love about a dirty job like oil drilling," he said, "but by God I do." He knew what his life was about and embraced it. I envied him.

An oil rig is a world unto itself, a primal space evoking childhood dreams of digging a hole to China in your parents' backyard. A weirdly intimate act, drilling makes the earth quiver up through your feet, but it sends your thoughts down into the hole. No matter how high-tech the modern drill rig becomes, it can't ever be removed from the subterranean grime of its primary work. Unlike a logger, a driller doesn’t smell like a pine tree when he’s finished, and unlike a cowboy he doesn't get to sit around a campfire at night. He lives, eats, and sleeps under the bright lights and grinding din of diesel generators. He stinks of oil and barite drilling mud and diesel fuel and sweat. The drilling goes on 24/7—deafening hours of roaring machinery—because every hour has an opportunity cost, and you’d better believe the company man is crunching those numbers.

When the well comes in, the relief and elation among the crew is overwhelming. Their faces beam, “We struck oil!” From the company man on down, they get a bounce in their walk and a ring to their voices, something that goes beyond the cynical desire for money. It's the clarity that comes from a job with simple definitions for success and failure: You either strike oil or drill a dry hole.

Then, when it's over, it's over. You leave nothing behind. Rigs are made to be taken down, made to be mobile. Most crews move into a field, drill a well, and move on. The generators cease their rumbling, the derrick and the rig floor are taken apart, swung away by crane and hauled off by truck or barge, bound for the next drill site. Just a wellhead remains.

Cross Island was no different. A year after we delivered the rig, we returned to lug it away. I looked for the driller from Oklahoma and finally caught a glimpse of him. He nodded to let me know that he remembered me, but we were both working, and we didn't speak. His face was the wild visage of a man who'd spent a dark winter above the Arctic Circle, working 90-hour weeks drilling for oil. He was one year more haggard and $100K richer. Over 10 years spent working tugboats in the arctic oil fields, I had many brief encounters like this: the casing man from Colorado, the tool pusher from Croatia, the specialty driller from East Texas—men who loved to tell stories, who’d been everywhere, drilled for everything, and stuck their faces into the earth.

When we’d finished our loading and pushed the barge east toward Flaxman Island, I wandered through the carcass of that dismantled rig. It had a lonely, a ghost-town aspect, with empty control rooms, stripped beds, silent generators, and the derrick tipped on its side in sections, like a broken monument to progress. Silent and in pieces, a drill rig inspires no wooden crosses for the carving of initials and dates, but somehow I was inspired. I wanted to freeze it all in place, to make my own record of the people I'd known there. If there’s anything to love about oil drilling, it’s the raw human spirit of those who do the work.

— David Masiel

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~••••ooooooo||||[O]||||ooooooo••••~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

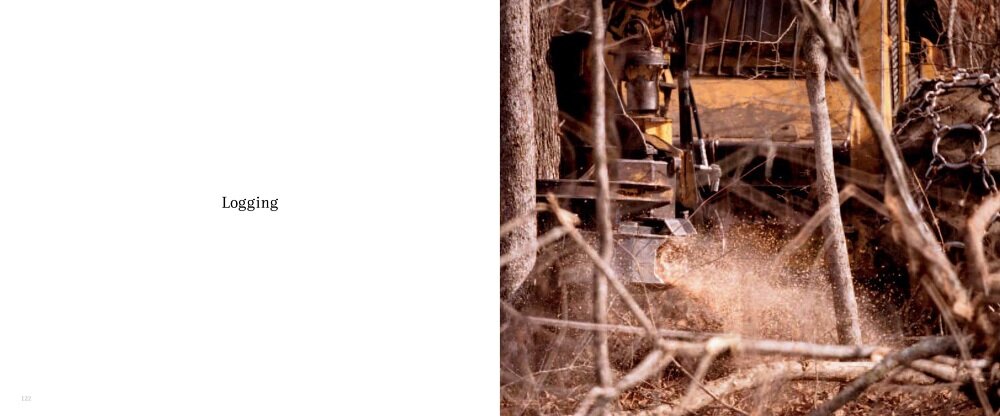

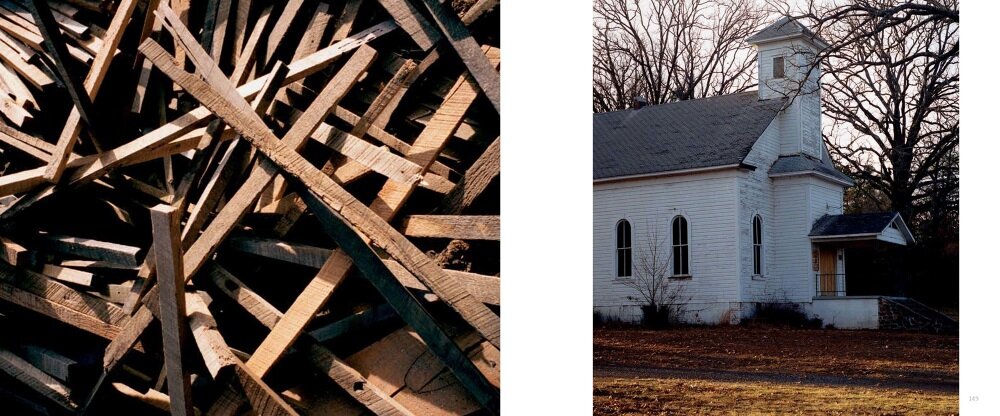

HAVE AXE, WILL USE IT

— Randy Wayne White

Many years ago, I took a weeklong class to learn how to climb trees and telephone poles of various sizes. Like me, most of the students were telephone contractors, but a few were professional lumbermen sent by logging companies for a refresher on safety.

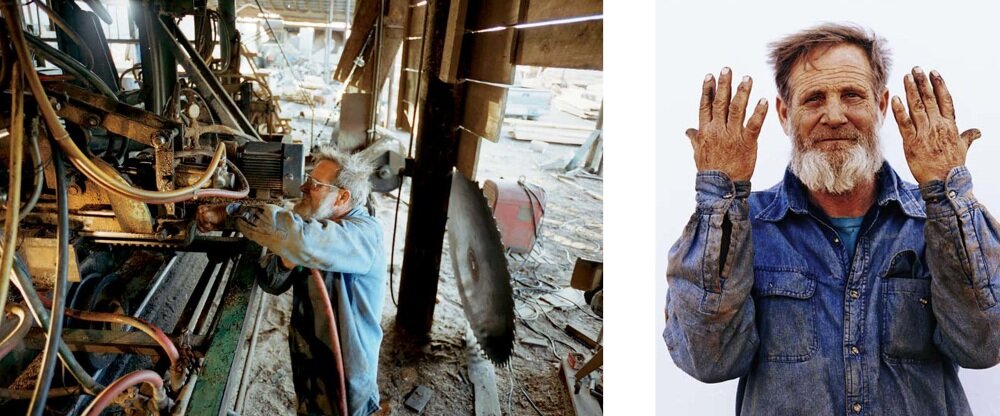

The lumbermen (always said as if the “L” were capitalized) were easy to spot. They wore serious, calf-high work boots, weathered to a cowpoke gray. The rest of their gear, though—leather climbing harnesses, straps, and tool belts—was stained neat's foot–red from wear and meticulous oiling.

They were the pros. Us phone guys were dilettantes by comparison, a fact the lumbermen reinforced with languid attitudes as they breezed through the course requirements. They already knew the basics—like how to sharpen gaffs (metal climbing irons fitted with a single, arrow-shaped spike that attach to one’s boots) and at what angle to bury them into the wood when ascending and descending. More advanced knowledge, like how to pass a safety belt around a tree and secure the spring-loaded D-ring before leaning back comfortably ("belting in"), was second nature. And none of them ever "burned a pole” by improperly sinking in the gaffs and slipping into a free fall while still belted in to the pole—a humiliating gaff gaffe the rest of us struggled to avoid.

On the last day, to graduate, we had to climb to the top of a 40-foot pole, belt in, and play catch using a basketball. If you made a bad throw or dropped a good throw, you had to climb down, fetch the ball, and then ascend carrying the damn thing. There were about a dozen students, and our “classroom” consisted of twice that many poles planted in a circle. High in our wooden Stonehenge, we threw the ball around like a horde of NBA-crazed druids, with the lumbermen taking special joy in it. They’d purposefully make crappy throws and then race each other to get to the ball. I can’t hear the word lumberman (or lumberjack or logger) without thinking of their languorous expertise at climbing poles. And I still wince at the nightmare of burning a pole. After graduation, the lumbermen continued plying their trade, while I quit the phone company and let my woodcraft skills lapse. I ended up publishing 13 books instead, and using vast amounts of paper in the process.

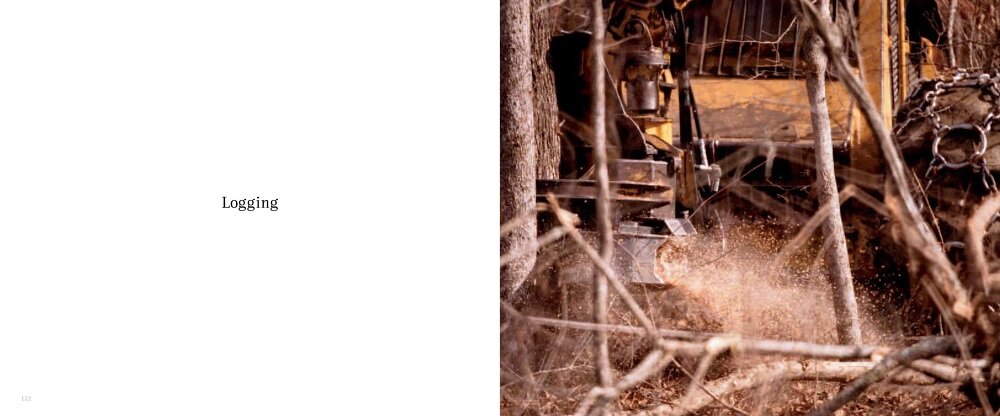

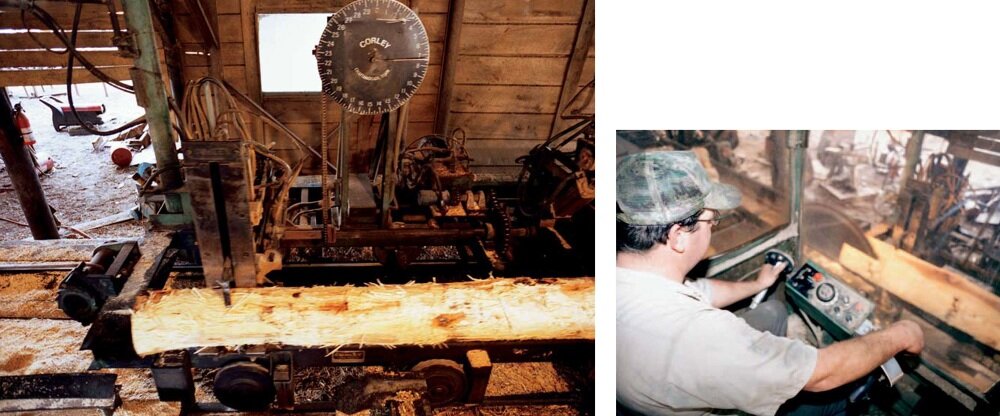

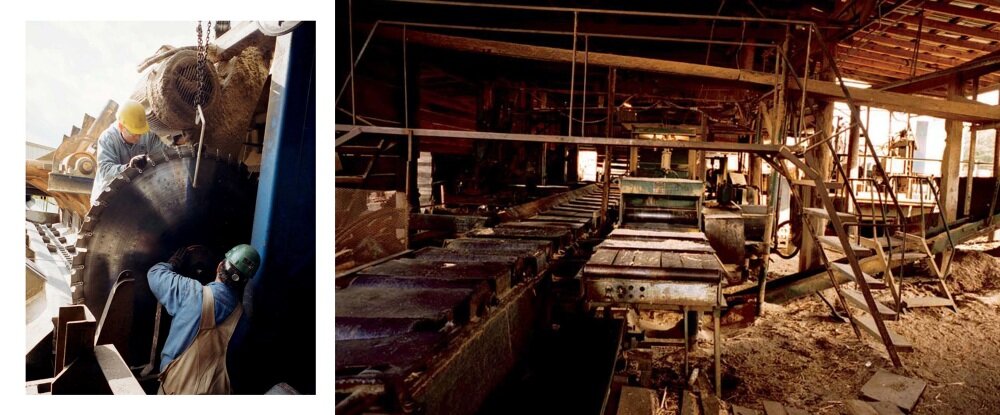

America has long been a world leader in the production of timber and wood pulp, used for making paper. In fact, America’s first exports to the British Isles and Europe were ship timbers and masts. The tools of logging have since become mechanized, but the basics remain the same—felling timber and delivering it to sawmills; milling logs into boards or for use in byproducts like pulp, plywood, pine tar, and mulch; grading boards according to quality and intended use; and drying, treating, and finishing the wood. Once the masters of axes and crosscut saws, today's loggers are more familiar with high-tech machines like diesel feller-bunchers designed for cutting, hauling, and stripping raw timber. But lumbermen still need to know how to clamber 60 feet up a tree, chainsaw in hand, and fell the top-heavy canopy so it can safely be cut down.

Logging pushed America’s frontier boundaries ever-westward and tragically contributed to the deadly head-on collision with North America’s indigenous peoples. European settlers seeking freedom and a fresh start appropriated land and felled trees to create space and light for ranching, pasture, and agriculture. First it was Maine, then Oregon, Washington, and California became bastions of the burgeoning lumber industry. More recently, the forests of the southern states have provided the bulk of the industry’s trees.

And make no mistake, the lumber industry is an industry. Trees are treated as a product—a crop, like corn or wheat—and forests are managed for maximum yield, with clear-cutting being the most controversial technique. Tree planting and other more sustainable practices are, however, on the rise. Finished lumber for construction is primarily milled from fast-growing coniferous needle-bearing species like pine, hemlock, fir, or spruce.

Stored in the most primitive segment of our brains, scientists say, is an ancient knowledge of how to survive, a genetic memory that resides in the proteins of the DNA helix. For many of us, wood smoke or the percussive thwack of an axe at work keys a primal stirring—the need to harvest trees for fuel and shelter. Echoes of our ancestral past still prompt us towards action.

For a time, lumbermen represented North America's masculine ideal and were idolized in old films, heroic tall tales like those of Paul Bunyan and his ox Babe, and in advertisements, like those for Brawny paper towels. Flannel shirts still exude an aura of manliness. But thanks to logging practices that have laid waste to wilderness, causing erosion and destruction of waterways, this image has changed substantially. An article in The Wall Street Journal about the nation's worst jobs placed lumberjacking at the top of the list. The occupation couldn't be much rougher in terms of pure danger. Stand belted atop a tree with a storm approaching and winds gusting (as I have) and you’ll seek new employment too.

Yet, these hardy woodsmen persist.

Their dedication to a profession that requires so much skill, courage, and plain, bull-headed toughness suggests that logging is more than a job. It is an American calling. — Randy Wayne White

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~••••ooooooo||||[O]||||ooooooo••••~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

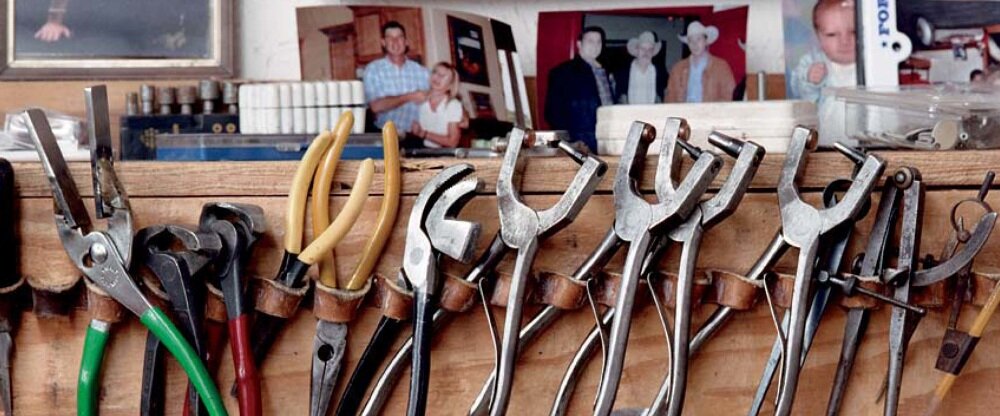

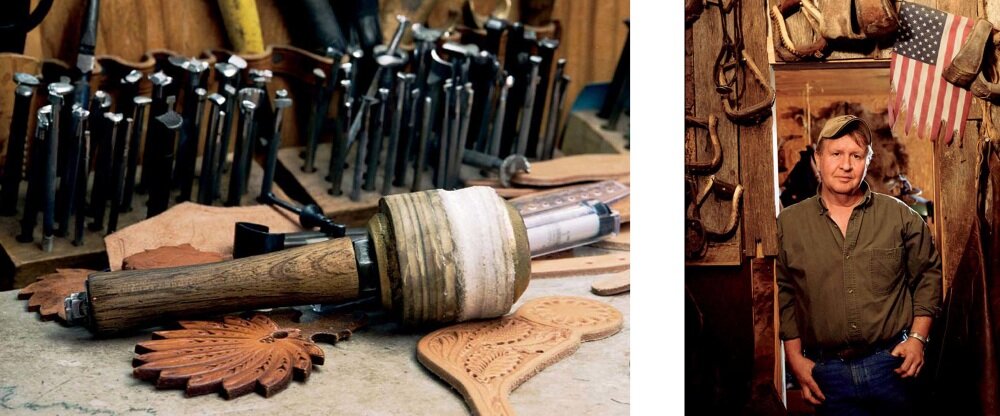

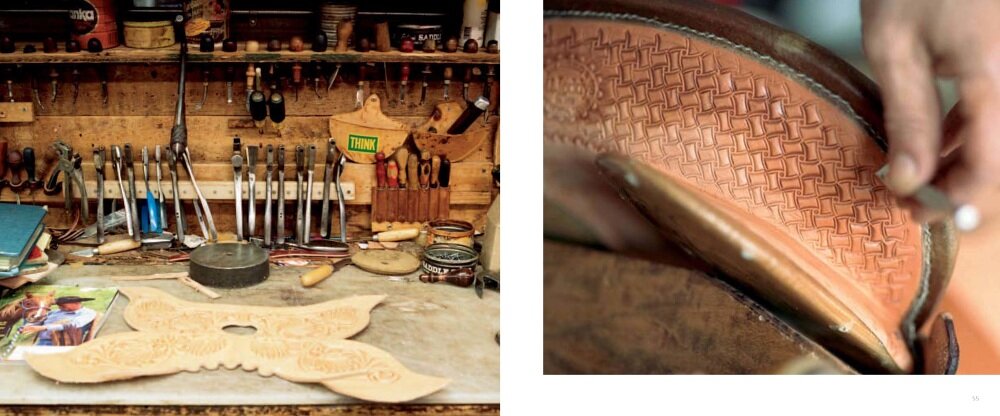

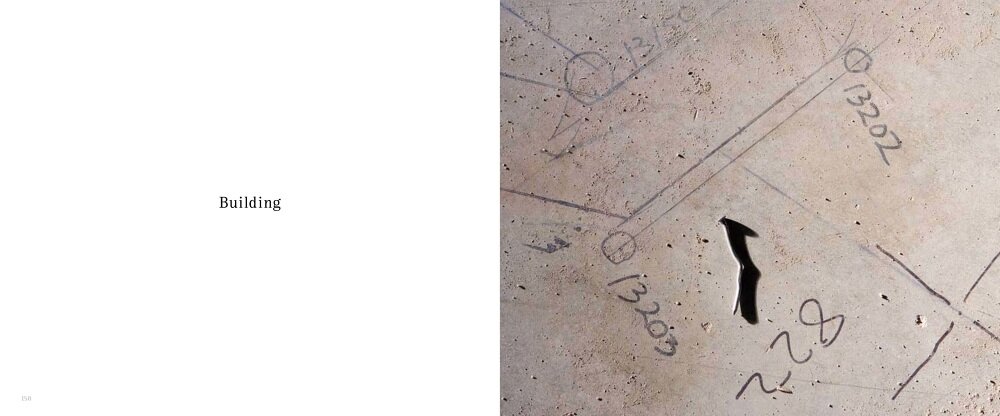

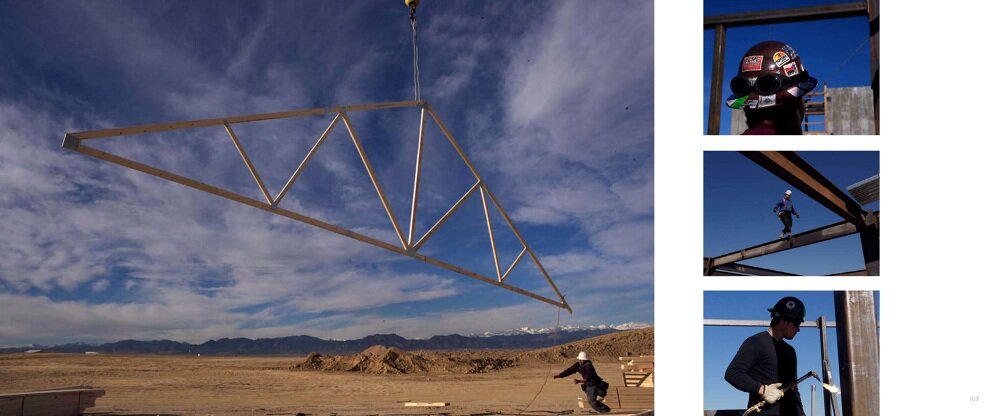

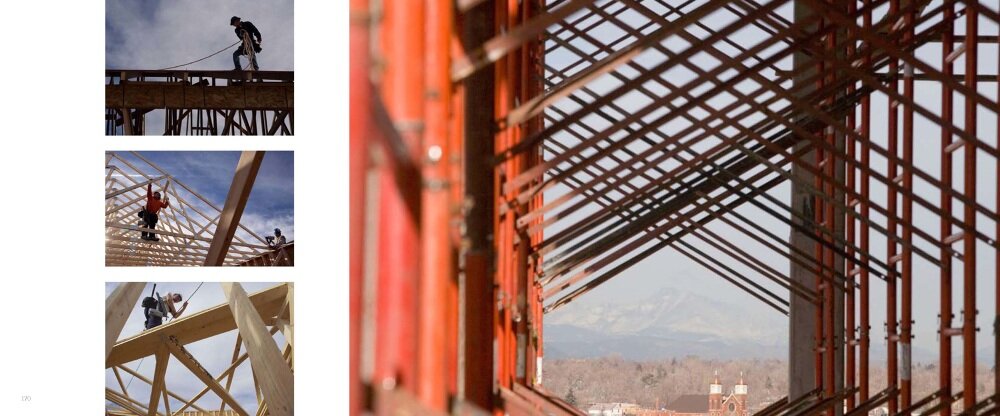

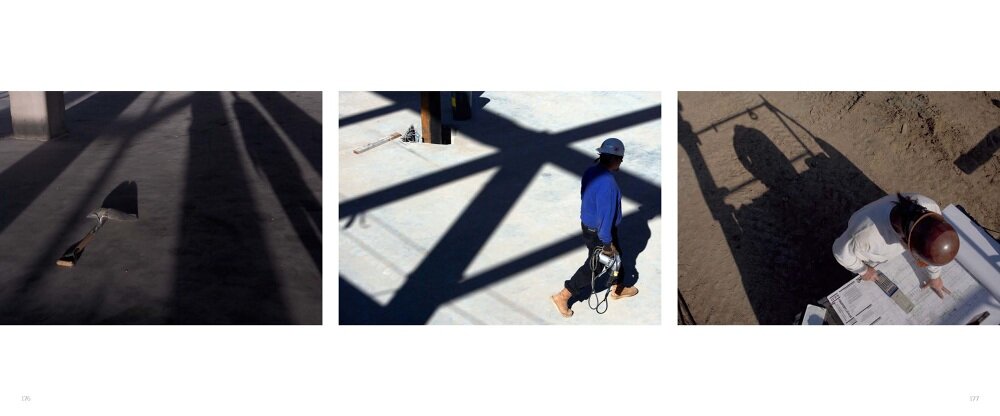

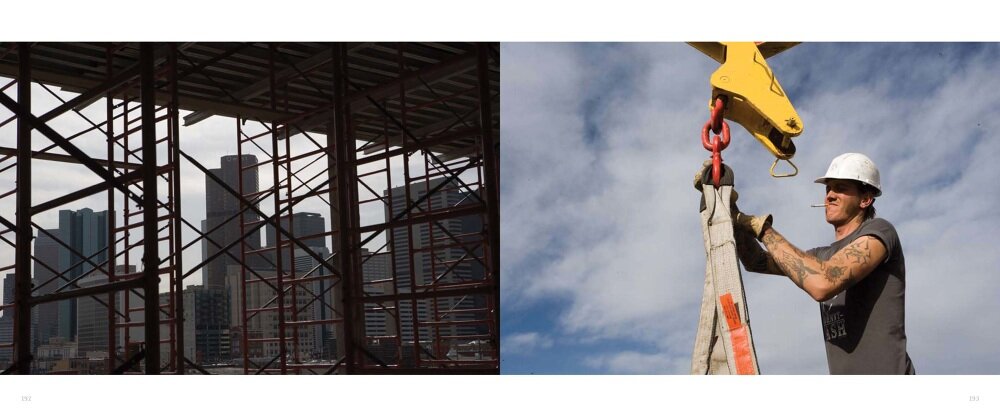

IMPLEMENTS OF CONSTRUCTION

— Philip Armour

“Tools are what make you money.” That’s what a tree trimmer once told me as I marveled at the gigantic chainsaw he was using to split a ponderosa trunk lengthwise. Five feet long, the outsized blade earned him jobs other trimmers had to pass up.

Five years later, when I walked onto a construction site in Taos, New Mexico, and asked the foreman for work, “What tools do you have?” was the first thing he asked me. Not enough, it turned out.

How much a builder has invested in tools is a sign of his skill. Why would anyone lug around a chop saw or a nail gun if he didn’t know how to use it? In the construction world, tools are the measure of a man (that, and the size of his truck) and earn him more work accordingly—and more pay. Despite being a hippie redneck who loved to party and ski, the Taos foreman, John Hunt, wore a cowboy hat tight over his ears and had a house to build and no favors to give.

The friend who had introduced me, a former employee of Hunt’s also looking for work, spoke on my behalf. Reluctantly, Hunt took us both on. I would be allowed to occupy the very bottom of the crew’s totem pole, menial laborer, and my friend was told to keep an eye on me. But we were building a passive-solar strawbale house, which required more toil than precision carpentry, so I fit right in.

A construction site is meritocracy at work. It being winter, Hunt appreciated that I relished hard work, did as I was told, and didn’t complain when he abused me like a rented camel. Conversely, he fired two guys whose work didn’t show the skills they’d claimed to have. Builders that try to apply the phrase “fake it till you make it,” reveal gross incompetence, not pluck. Padding your résumé leads to expensive mistakes on a jobsite, like crooked stairs, and earns you scorn.

In fact, an inexperienced worker has to admit that he knows nothing before anyone bothers to teach him. That’s because measurements like “straight” and “level” are not open for interpretation. Tiny mistakes get magnified as you build up, ultimately resulting in disasters like misaligned walls. Furthermore, the apprentice must be humble before the master imparts esoterica. Hunt’s trick of grinding the ridges off hammerheads, for instance, saved my fingers from compound damage when I inevitably struck them.

I admitted to knowing lots of nothing; and over a period of five months, Hunt moved me from sifting sand for cement to sanding boards for the ceiling to hammering out simple carpentry assignments to plastering walls with a hawk and trowel. He patiently taught me along the way and gave me two unsolicited raises.

At 12:30 p.m. our five-man crew would drop the tools and sit on the house’s sun-baked south side for thirty minutes of bag lunches and jawing. Our jobsite was miles out of town on a high-desert mesa surrounded by emptiness and sagebrush, so leaving for lunch wasn’t an option.

“I love this job,” Hunt said one day to no one in particular. “You get to dress like a slob and sit in the mud and nobody rags you about it.”

“You’d be a slob even if you weren’t a builder,” I pointed out.

“Ha! You’re right.”

We were paid in cash every Thursday afternoon, and the lure of this financial arrangement and the trailless existence it implied attracted a quirky bunch. There was Luke Nichols, known for being the son of New Mexico novelist John Nichols, author of The Milagro Beanfield War, and for periodically vanishing down to Mexico; Auggie, the laconic Texan ski bum who got me the job; a chain-smoking kid from the South; me, an enviro-fascist with a gigantic beard; and John Hunt himself, ripped like an Olympic wrestler and playful as a teenager.

Doing the job right was one thing—Hunt despised buildings with “hippie skirts,” his expression for cement plaster that sagged from lazy application—but as long as we pulled our weight, he cut us slack. If anyone showed up to work hungover, he would send him home, no questions asked. Hunt would let us shoot his rifle at the port-o-potty and loved to rile up the pack of dogs always milling about the site. When Hunt’s own collie-mix, the usually gentle Iris, caught and ate a rabbit, grotesquely soiling her white fur red, she was solemnly renamed Bloodmane. And when it snowed, we’d ski.

We were a band of mercenaries, and the house was our battleground. The labor was hard and dangerous and no one had insurance, so it took just as much bravado to risk getting hurt as it took skill to avoid it. Serious stamina and steely confidence were needed to carry boards and brick and bales up and down ladders in muddy boots and across the snow-covered roof. No one leaned on bravado more than Nichols, who swore like a sailor to motivate himself and constantly argued over what stations play on the radio.

“Jesus, why do you always sound so pissed off?” I asked him once.

“You’ve got to stay mad!” was his answer. “That’s how you keep it going!”

But Nichols had a thoughtful side, too. Every day, he would slowly walk the job site and pick up nails. “I hate getting flat tires,” he explained the first time I noticed him wandering about, head down.

In a way, our entire crew exhibited Nichols’ spirit of practical thriftiness by endorsing passive-solar construction, thick-walled buildings made to absorb solar energy. We were disdainful of “sticks” (two-by-fours) and preferred building with adobe, straw bales, pumice-crete (pumice aggregate and cement), and even car tires rammed full of earth—all massive structures that cost little to heat and cool.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the number of people working nationwide in residential construction industry is about 980,000, of which builders using alternative materials are a scant few. But Hunt was totally committed to building green and went so far as to make a solar-powered generator. He would haul it to jobsites and use it for running power tools. This was no lark, mind you. Hunt did a brisk business selling his custom-built homes for $300,000 plus.

My bad back and an ugly, 7a.m. coffee-and-cigarette habit I grew to despise, but need, eventually prompted me to apply to graduate school. Hard labor made central heating and a desk job sound pretty damn nice. These days, my tool of choice is a svelte laptop computer, while Hunt continues to wield solar-powered tools for a better future.

— Philip Armour

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~••••ooooooo||||[O]||||ooooooo••••~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~